To what extent does economic dependence inform the anachronistic practice of female genital circumcision in Africa?

Abstract.

Female genital circumcision is a procedure that requires the excision of some tissues that form the female genitalia. It is an old tradition that exists predominantly in Africa, and has, of late, become a very contentious and controversial issue in the international community. There are various grounds for this controversy, one of which is the contention by rights advocates that female circumcision is gratuitous violence against women in the form genital mutilation, and should be abolished. Cultural relativists counter that female circumcision is a traditional ritual that defines cultural identity, and hence outside the competence of international bodies with Western liberal sensibilities. This work examines female genital circumcision as practiced in Africa, and its legitimacy within the context of modern human rights regime. My method of inquiry consists of a thematic analysis of this practice as it touches on United Nations’ conventions, and an ethnographic approach that seeks meaning through interpretation of cultural observances.

My thesis adopts the position that female genital circumcision is a dangerous practice that violates accepted precepts of international human rights. But since no single factor can fully explain its practice and prevalence, a successful challenge would necessarily be multifaceted, and at the same time mindful that any effort to enforce internationally recognized rights may come in conflict with other equally important rights, such as those of religion and cultural minorities. Thus, national governments have a duty to carefully balance other sets of important rights against the need to protect fundamental human rights of girls and women.

Prologue

Ms. Kasinga hails from a northern village of Togo comprised of the Tchamba-Kunsuntu tribe. Young women of this tribe are, as part of the tribe’s traditional observances, circumcised by the time they are fifteen to prepare them for marriage. Kasinga’s father, an influential man in the village, protected her from this practice until his death in 1992. His sister (Ms. Kasinga’s aunt), by tradition, assumed full responsibility for the welfare of his children upon his death, and subsequently forced Ms. Kasinga’s mother out of the family home. The aunt then arranged a polygamous marriage to a man, and together they brought pressure on Ms. Kasinga, then 19 years old, to get circumcised. Ms. Kasinga fled to the US, and promptly petitioned the US government for asylum under the United States refugee Act of 1980.

For Kasinga’s petition to be successful, she must be able to prove two things: (1) that female genital circumcision is indeed a form of physical mutilation that falls under the category of “persecution” which the Refugee Act defined as “the infliction of pain or suffering by a government, or person a government is unwilling or unable to control, to overcome a characteristic of the victim,2” and (2) that the persecution she feared was directed towards an identifiable group to which she belonged. By narrowly tailoring the elements of the Refugee’s Act to the particulars of her case, Kasinga was able to convince the Board of Immigration Appeals in 1996 that she belonged to a social group of young women of the Tchemba-Kunsuntu Tribe who have not had genital circumcision, and who are opposed to the practice3. The Board, relying on the ‘test for a social group’ established in an earlier case (the Acosta case) held that gender and tribal affiliation are immutable characteristics, and that an intact genitalia is a characteristic so fundamental to the individual identity of a woman that she must not be obligated to alter it4. This ruling was a powerful precedent, and continues to guide immigration judges in cases based on Female Genital Mutilation.

The Kasinga decision ignited a heated debate in academia, amongst human rights activists, and international agencies such as The World health organization (WHO)5. Human rights advocates argued that fundamental human rights are universal, and thus transcend all local cultures in conflict with basic rights6. Cultural relativists weighed-in, and argued that defining female circumcision as persecution amounts to a challenge to the cultural autonomy of groups in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula that engage in such practices7. The World Health organization called the practice a ritualized violence that violates universally recognized human rights standards8.

Introduction

The chief concern of my thesis is female genital circumcision as practiced in Africa, and its legitimacy within the context of modern human rights regime. The approach I adopt in this inquiry would include a thematic analysis of this practice as it touches on United Nations’ Conventions; and an ethnographic inquiry that approximates what Clifford Geertz9 has labeled as ‘thick’ description, a method of study that seeks meaning through interpretation of cultural observances. This would necessarily include a narrative of my experiences as a young man growing up in Nigeria where the practice of female circumcision is prevalent, and the field work of Janice Boddy in Sudan.

At the heart of this inquiry is the tension between human rights advocates on the one hand, who strongly adhere to the view that human rights are universal and may not be attenuated to accommodate cultural peculiarities, and on the other, cultural relativists with their argument that the imposition of a universal standard of rights marginalizes the cultures of indigenous groups. Embedded in this tension is a group of issues, one of which is female genital excision or what is now commonly referred to by abolitionists as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). My thesis posits that female circumcision is an unnecessary and dangerous mutilation of the body that violates accepted precepts of international human rights.

The next sections of this work would discuss its practice and prevalence, the dangers associated with its practice, and those most likely to engage it. These would be followed by an analysis of how female circumcision violates the norms of modern human rights regime; and a brief discussion of universal human rights and cultural relativism. The last section concludes with recommendations on how to curb its practice.

Practice And Prevalence

The practice of female circumcision is an old tradition in at least 28 countries in Africa and Asia; and generally performed, presumably, to prepare young girls for womanhood and marriage. Lately, however, this practice has surfaced in immigrant communities in North America and Europe11. Before the advent of Western medicine, all circumcisions were performed without the benefit of effective anesthetic, and under septic conditions; in countries where it is still prevalent, this is still the case, and often performed by lay practitioners without any medical background. The rationale for the practice is all too familiar – it conduces to good hygiene, promotes fertility, and discourages promiscuity. Generally, girls are subjected to this experience between the ages of five months to ten years. However, as more of the general population gained access to formal education, the practice in the mid 1960s became almost nonexistent amongst the middle class.

By the 1970s, female genital circumcision was confined exclusively to villagers and peasants. While practices vary widely, there are three basic forms of genital circumcision. One is essentially a clitoridectomy, where part or all of the clitoris is amputated, the second is an excision that involves the removal of the clitoris and the labia minora; the third is the most severe, and is what is commonly referred to as infibulation. This requires the excision of the clitoris and the labia minora, the labia majora is cut and then stitched by the edges, the legs are then tied together until the wounds heal. When the wounds heal, scar tissues join the labia and cover most of the virginal opening, barely enough to allow the flow of urine and menstrual blood. In this regard, Janice Boddy gives an account of her experience in the Suadanese village of ‘Hofriyat’:

Though conventionally termed “circumcision,” the procedure is not physically equivalent to the like-named operation performed on boys. In Hofriyat, male circumcision entails removal of the penile prepuce, as generally done throughout the Middle East and, indeed, the West. Pharoanic circumcision, however, is more extreme, involving excision of most external genitalia followed by infibulation: intentional occlusion of the vulva and obliteration of the vaginal meatus. It results in the formation of thick, resistant scar tissue, a formidable obstruction to penetration. A less severe operation, structurally similar to that performed on boys, is currently gaining ground in Khartoum…. This is referred to as masari or sunna circumcision and consists in removing only the prepuce or hood of the clitoris…. While realizing that it is less harzadous to health than pharaonic circumcision, they continue to oppose it on aesthetic and hygienic grounds and in this lies a clue to its deeper significance. Several women I questioned in 1984 made their feelings graphically clear: each depicted sunna circumcision by opening her mouth, and pharaonic, by clamping her lips together. “which is better,” they asked, “an ugly opening or a dignified closure?” Women avoid being photographed laughing or smiling for precisely this reason: orifices of the human body, and particularly those of women, are considered most appropriate when closed or, failing that, minimized.12

For those who survive the ordeal, the pain from damaged nerve endings never goes away, and remain susceptible to urinary tract infections13. For those who continue to reinfibulate after each birth, the opening gets smaller, thus raising the likelihood of menstrual blockage and obstruction of the urethra which in turn may lead to reproductive tract infections and compromised fertility14. Janice Boddy again gives an account of what circumcised Sudanese women in ‘Hofriyat’ must endure:

A young girl both dreads and eagerly anticipates her wedding day: she welcomes the elevation in status while fearing what it implies, having to endure sexual relations with her husband. Informants told me that for women circumcised in the radical manner, it may take as long as two years of continuous effort before penetration can occur….. Because they find it so painful, many of the women I spoke to said they avoid sex whenever possible, encouraging their husbands only when they wish to become pregnant ….. Sexual relations do not necessarily become easier for the couple over time. When a woman gives birth the midwife must be present not only to cut through the scar tissue and release the child, but also to reinfibulate her once the child is born.15

But in spite of the inherent risks, practitioners look at the practice as an integral part of their culture and ethnicity. But what is culture, and how does one begin to understand symbolic representations and behavior of a people? Geertz asserts that “culture is context16,” and propounds that in order to understand it, one must see things from the point of view of the natives – “our formulations of people’s symbol system must be actor-oriented17,” but acknowledges that our interpretations are of themselves interpretations of the native’s.

Rationale for female Circumcision And Unresolved Tensions

Anthropological and ethnographic studies of female circumcision have all pointed to an array of reasons commonly adduced by practitioners in twenty-eight African countries18, they include: compliance with religious precepts, protection and preservation of ethnic and group identity, promotion of good health through cleanliness, protection of family honor by preventing sexual promiscuity, and preparation for womanhood and marriage. In communities where religious grounds are the main motivation for female circumcision, Islam is the predominant religion, even though there is no direct mandate for it in the Koran19. While the Koran recommends chastity for women as a worthy moral value, it does not explicitly instruct believers that circumcision is the means to achieve this objective20. Some researchers have made note of the fact that in Saudi Arabia, presumably the center of Islam, female circumcision is not prescribed; indeed some have traced the earliest known evidence of female circumcision to Egypt in a period that predates Islam, thus supporting the notion that the practice has Pharaonic rather than Islamic beginnings21.

For many practitioners in Nigeria and Togo, the need to protect ethnic identity, and the foreclosure of sexual promiscuity resonate in the majority of communities where the practice is prevalent. For, in these communities social status, privileges, and respectability are often established by rituals such as circumcision, and with heightened social standing females become more attractive and eligible for marriage. But there is also the issue of abiding by, and sustaining local custom and tradition; as one Somali woman puts it ‘if you stop a tradition, it’s similar to making God mad22.’ Thus, in many instances strict observance of customary practices are held above all other human endeavors, and come to define daily existence.

One of the more contentious and enduring aspect of female circumcision is the claim that Westerners approach the issue from an ethnocentric, and colonial interpretation23. Thus, communities where the practice is prevalent take offense from the implication that change can only come from Western intervention. Feminists engaged in this struggle also face a very serious dilemma, and that is how to forcefully argue against a practice that is principally conducted by women, and known injuries are inflicted by women on other women. Given the cultural dimension of female circumcision, any argument against its practice tends to invoke the overtone of cultural elitism, and disregard for others’ culture. Ellen Gruenbaum addresses these issues in her study of female circumcision in Sudan by using what she termed a ‘contested culture approach’ that highlights a culture’s internal contradictions by encouraging debates amongst different classes, gender, and social divisions24.

Gruenbaum disputes the commonly held view that female circumcision is practiced to control a woman’s sexuality, and contends that the sexuality of Sudanese women that have undergone circumcision is ‘neither destroyed nor unaffected’ and that circumcision does not totally eliminate sexual satisfaction of circumcised women25. As to the possibility of enduring psychological scarring, she found that adult women in Sudan “could recall their circumcision vividly, but most did not dwell on the pain or fear except to laugh about it.”26 While several factors may help explain the prevalence of female circumcision in Africa, Gruenbaum found that in some instances it serves as an ethnic or social mark, and the more severe the procedure is the higher the social status of the recipient27. She also asserts that the most often cited reason for circumcision is marriageability28; for marriage remains a significant means of achieving desired social standing in the absence of other more modern symbols of achievement such as education and employment.

Another significant aspect of this debate is the right of parents to raise their children in accordance to received customs and traditions. A parent who subscribes to the practice of female circumcision, perhaps in deference to local custom, may strongly believe that the welfare of the child would be abridged if left uncircumcised, and thus harbor a sense of guilt for not exercising her parental responsibility. For she sees the practice as a social and cultural right that inures to the child; the idea that the practice may be seen by outsiders as child abuse is far removed from the calculus since the procedure is presumed to be in the best interest of the child. Children, however, are generally adjudged incapable of making informed decisions in matters that touch their welfare; given this presumption of ‘diminished capacity’ a child cannot be said to have exercised her free will when she undergoes the surgical operation of circumcision. It is on this basis that rights advocates see circumcision as violence against children, and an abuse of guaranteed human rights. And herein lies the conflict between the right of parents to raise their children in conformance to customary observances, and the right of the child to be free from potentially harmful practices.

With regard to adult female circumcision, it is not altogether clear that consent was given ‘freely.’ Social conditioning, peer pressure, and the prospect of life without a husband are strong influences on the adult female in regard to the issue of circumcision. As in the case with the child, the adult female has no real choice in the matter; thus with full knowledge of the health risks and pain that accompany the procedure, and equally cognizant of the social and economic consequences of not being circumcised, she is faced with no better alternatives. Since no single factor can fully explain the practice and prevalence of female circumcision, successful challenges to its practice would necessarily be multifaceted, and mindful that any effort to enforce internationally recognized human rights may come in conflict with other equally important rights, such as those of religion and cultural minorities.

Human Rights Implications of Female Genital Circumcision

The rationale given by practitioners in Nigeria, Sudan and elsewhere for female circumcision are almost identical. As earlier suggested, the idea that circumcision conduces to purity, fertility, or chastity is a common ground invariably adduced by the natives. If the procedure did not come with unimaginable pain that boarders on inhumane treatment, the practice may have remained unnoticed by human rights advocates both in Africa, and in other parts of the world. If the associated health risks, when compared to assumed benefits, were marginal the practice may also remain under the radar of international women’s organizations. But this is not the case; from my personal inquiries of my relatives and my wife, there is strong indication that the presumed benefits, with the exception of chastity, are imaginary; the practice cannot be shown to have increased the fertility of women because uncircumcised women are found to be just as fertile. The best that can be said about purity and fertility is that they mask the real reason for the practice: in patrimonial societies where men have perennially subjugated the rights of women, this was just another means by which control is exerted. Men simply want their women to remain ‘pure’ by making leisure sexual activities very painful for women; this is especially true for the most severe form of circumcision – infibulation. And to guarantee chastity long after marriage, the women are reinfibulated after each birth. Here again is Boddy’s interpretation of her informants’ rationale for the practice in Sudan:

There exists a broad range of explanations for infibulation which together form a complex rationale that operates to sustain and justify the practice. Among them, however, those which refer to the preservation of chastity and curbing of women’s sexual desire seem more persuasive, given that in Sudan, as in elsewhere in the Muslim world, the dignity and honor of a family are vested in the conduct of its womenfolk…. Hence the need for circumcision to curb and socialize their sexual desires, lest a woman should, even unwittingly, bring irreparable shame to her family through misbehavior.29

When subjected to the principal doctrines of modern human rights regimes, female genital circumcision looks suspiciously brutish, hence the new designation by human rights advocates— Female Genital Mutilation or FGM for short30. Beginning with the 1948 articulation of rights declared in the United Nations’ Universal declaration of Human Rights31, feminists and rights advocates have relentlessly sought the elimination of female circumcision32. As early as the 1950s, African medical practitioners and activists have brought to the attention of international bodies such WHO and the UN the health risks of female circumcision33. It was not, however, until 1979 that a formal policy statement on this issue was made in an international seminar held in Khartoum34. The seminar focused exclusively on traditional practices that affect the health of women and children, and at its conclusion issued recommendations to governments that require the elimination of female circumcision.

In 1984, the African Women’s organization met in Dakar, Senegal, to discuss female circumcision35. The outcome was the formation of the Inter African Committee Against Harmful Practices (IAC); the goal was to forcefully bring to the attention of African Governments the harmful effects of female circumcision36. These initiatives led to the adoption by the UN of such treaties as the Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child37. Article No. 19 of the Convention of the Rights of the Child provides that all state parties:

….shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child against every form of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care of parents(s), legal guardian(s) or any other person who has the care of the child.38

Article No. 24(3) of the same convention issues this directive: “State Parties shall take all appropriate measures with a view to abolishing traditional practices prejudicial to the health of children.39” To many human rights advocates, the reference to ‘traditional practices’ in Article 24(3) is interpreted to refer principally to FGM40. Finally, the African Charter on Rights and Welfare of the Child adopted strong language that addressed the practice of female genital circumcision41. In Article 21(1) of its Charter it states:

State Parties to the present charter shall take all appropriate measures to abolish customs and practices harmful to the welfare, normal growth and development of the child and in particular; a) those customs and practices prejudicial to the health or life of the child, and B) those customs and practices discriminatory to the child on the grounds of sex and other status.42

But it was not until 1994, in the International Conference on Population and development held in Cairo that a formal body explicitly used the term ‘female circumcision’ in its policy pronouncements; and declared it a “violation of basic rights,” and requested of all governments to ‘prohibit and urgently stop the practice wherever it exists43.’ In 1995, The Fourth World Conference on Women, held in Beijing declared the practice a violation of women’s rights, and a serious threat to their reproductive health44.

A Brief Discussion of Universal Human Rights And Cultural Relativism

Modern human rights activism, while remarkably successful in many areas of relevance, is needlessly burdened by the presumed absence of a coherent and sustainable theoretical foundation on which to erect the principles of rights that would have both universal appeal and acceptance45. In substance, detractors and well-meaning proponents propound that the notion of universal human rights is flawed for two principal reasons: (1) it is based on Western democratic ideals of individual rights and freedom, and thus inappropriately hegemonic, and disrespectful of other cultures; (2) the primary ground on which rights advocates have based their demands – human dignity, is not justifiable except on religious basis46. The former, forcefully advanced by cultural relativists, is more serious and remains attractive to significant audiences in both developed and third-world nations.

The thesis here espoused is that female genital circumcision as practiced in many African countries is a violation of rights when examined within the context of modern human rights regime. This thesis is anchored on the notion that certain human rights are primary and fundamental, and may not be derogated from regardless of the kind of society or culture in which they first gained prominence. Furthermore, once such rights have attained near universal acceptance, either in law or practice, no ontological justification is needed for their being. However, some human rights as currently formulated, and because of their ‘secondary’ nature must be allowed considerable time to become malleable to domestic practices, and even then, may never enjoy universal acceptance in a specific form.

Human Rights and Cultural Relativism

Striped to its bare essentials, the primary objective of human rights is to confer on individuals a certain degree of dignity that enables free exercise of will, to engage in meaningful and sustaining relationships, to be free from harm, and to enjoy the freedom to pursue objectives that will enhance personal welfare without subjection to the indignity of physical and spiritual domination. This ‘certain degree of dignity’ properly stems from a sense of morality47. Put succinctly, human rights are ‘the equal and inalienable rights, in the strong sense of entitlements that ground particularly powerful claims against the state, that each person has simply as a human being.48’But these ideals are decidedly liberal and Western in origin, and owe significant intellectual debt to the seminal and revolutionary ideas contained in such documents as the American Declaration of independence of 1776, and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789. Collectively, these documents formed ‘the cornerstone of the political thinking of the nineteenth and twentieth century liberalism and progressivism.49’ Indeed, modern human rights regime may be rightfully categorized as an attempt to universalize the political and socio-economic liberal versions of rights. A glimpse of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides ample evidence for this claim. In parts of its preambles, it state:

Whereas the people of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom….. proclaims [T]his Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations50.

Undoubtedly, some human rights require relevant legal and social institutions to be meaningful and effective. Thus, countries previously within the sphere of influence of the erstwhile Soviet Union may find the argument for human rights vacuous since they lacked the requisite background and instrumentalities necessary for modern human rights regimes. But this is not to say that because these countries are wanting in the essential social institutions, they are therefore undeserving of the benefits of human rights. To the contrary, it is in these countries, more than anywhere else (except for the totalitarian regimes in Africa, Asia, and Latin America) that human rights law can produce significant immediate benefits, and create long-term conditions for social and economic growth. Fernando Teson makes this point quite eloquently when he propounds that “it is perfectly legitimate for a Westerner to advocate universal human rights and to discuss the possibilities for their protection worldwide. Human rights are about protection of people’s lives, safety, and individual freedom. They are a supreme universal value in the sense that most people, deprived of these protections, want to have them regardless of the culture in which they live.51” The point to be emphasized is that certain human rights are primary and fundamental, thus regardless of where their articulation hails from, their value remains universal and independent of cultural observances. The source of these rights, says Donnelly, “is man’s moral nature … Human rights are needed not for life but for a life of dignity, that is, for a life worthy of a human being. Human rights arise from the inherent dignity of the human person.52

This justification for human rights seems sensible, at least to one with liberal sensibilities; but rights advocates around the world continue to face daunting challenges that question the theoretical justification for universal human rights. These challenges come in the form of group rights, national sovereignty, cultural, and religious autonomy. This variety of claims underscores the philosophical doctrine of cultural relativism53; a doctrine that informs the strongly held conviction amongst its apologists that foreign actors should never interfere with purely domestic matters. This, of course, is based on the well- established norm of state sovereignty, and the philosophical supposition that only the ‘natives’ can solve problems pertinent to a culture. Thus, cultural relativism, in its complete sense, is often used to support the position that a particular articulation of human rights, even those of the most basic of rights, may be incompatible with cultural observances of other societies, and hence unacceptable54.

Cultural relativists are quick to point out that the notion of rights are universal; however, its articulation and practice vary and rightfully so amongst different cultures55. Every society, they assert, has a different idea of what constitutes ideal human rights, and that such ideal does not have to be consistent with those held in western democracies, and espoused by the United Nations. This position is succinctly and forcefully stated in a recent critique of human rights in Africa: “For countries that have not known peace, stability, or progress since their contact with the forces of Western imperialism, civil and political rights have no meaning.56. And herein lies the essence of the current debate; on the one hand rights advocates assert that human rights should be universal, and that all cultures are ultimately malleable to the liberal interpretation of rights; on the other hand cultural relativists insist that universalizing the concept of rights as articulated by rights advocates will be tantamount to a western hegemony, and a delegitimization of other cultures.57 They argue that different societies should be allowed to define and promulgate rights to the extent that their cultures permit. Both sides make compelling arguments, but they confuse the issues; primarily because they fail to identify the source of human rights.58

A Confusion of Natural Law and Positive Law

In human rights discuss, two kinds of law have always been invoked to lend credence to the various propositions adduced by the principals: positive law and natural law. Positive law, in its popular apprehension, is the sort that different jurisdictions enact to govern conduct, and enforced by the police and the judiciary. But these laws are relevant only to the affairs of citizens within a particular jurisdiction, and are such not human rights. Thus, as a citizen of the US I can point to the Bill of Rights as the basis for my claims or rights; but those who live in Columbia or Nigeria where there are no such enforceable constitutional guarantees to protect them will have no use for rights based on positive laws that do not transcend jurisdictional boundaries. A different sort of law is therefore needed to overcome this difficulty.

Natural law, in a special apprehension, provides a set of general moral standard on which claims, immunities, and liberties may be based without the constraints of jurisdictional limitations. These moral standard must necessarily be universal and independent of culture, religion, and nationality. Thus, it must be the case that a particular version of natural law must inform the claim of universal human rights. For if humans have rights by virtue of their humanity, it must be the case that there exists a general moral standard that is universally accepted, the particularities of its manifestations or understanding notwithstanding. This is what gives natural law its special advantage over positive law as a source of human rights.

Conclusion

In 1998 the World Health Organization estimated that about two million girls and women are circumcised every year.59 A study by the Kenyan government reports that over 80% of circumcised women experienced at least one serious medical complication from the procedure.60 In other notable studies conducted in other countries, researchers found that between 15% and 30 % of all girls circumcised die from infections and bleeding.61 The primary objective of human rights is to confer on individuals a certain degree of dignity that enable free exercise of will, to engage in meaningful and sustaining relationships, free from harm, and the freedom to pursue objectives that would enhance personal welfare without being subjected to the indignity of physical and spiritual domination.62 Since 1948 rights advocates have consistently argued that human rights should be universal, and that all cultures are ultimately malleable to the liberal interpretation of rights.63 On the other side of the fence are cultural relativists, who have also for long argued that universalizing the concept of rights as articulated by rights advocates will be tantamount to a western hegemony, and a delegitimization of other cultures.64 They argue that different societies should be allowed to define and promulgate rights to the extent that their cultures permit. Both sides make compelling arguments, and a compromise must be reached or the obstacles to a coherent and consistent universal observance of rights will persist.

The practice of female genital circumcision falls squarely within this debate, and clearly illustrates the kind of difficulties that rights advocates must overcome in their quest to universalize basic human rights. Unquestionably, there are certain human rights, such as the right to be secure in person, and freedom from civil, political and religious subjugation, that must enjoy the international status of jus cogens, regardless of domestic cultural observances. Female circumcision comes with a high risk of physical endangerment, and must be strongly condemned, and discouraged. But it is the outcome of a powerful tradition that permeates most of Africa, and some religious observances. While Westerners may find this practice abhorrent, it remains a right of passage for many, hence the need to seek the most effective approach to curb its practice is imperative; but the approach taken must also be, at once, equally sensitive to cultural and religious sensibilities.

A starting point in this campaign should be the enlistment of national governments in countries where circumcision is prevalent; such enlistment is critical for the simple reason that national governments have the capacity to carry ‘carrots’ or wield the ‘stick.’ The ‘stick’, however, must always be the last resort in all human rights discourse. This should be followed by a concerted effort to educate the relevant population and people in responsible offices, such as traditional and spiritual leaders, on the health risks of circumcision, and the attendant inhumane treatment to recipients. If this fails, then an alternative ritual that approximates the same need may be adduced; and with patience, the old practice of female circumcision may gradually fade away. Criminal sanction cannot be a viable solution in this case, for it fails to address the fundamental reasons for the practice; and unless those reasons are properly addressed, the practice will continue, albeit out of public view, even with the prospect of severe sanctions.

While the ideals of human rights are admittedly western and liberal in inclination, their substantive values and usefulness are not limited to societies that espouse western ideas, but are rather just as meaningful and useful to non-Western societies. The common bond of humanity makes these ideals non-parochial, and imbues them with universal qualities. The fact that individual rights and freedom were first comprehensively articulated and formalized as principles of governance and conduct by Western societies is not enough to make them objectionable to other cultures as long as experience has shown them to be salutary to individual welfare and societal progress. By way of example, the idea that man can fly, and hence the invention of modern air travel, is of Western origin. The benefits from air travel are unquestionable; should non-Westerners now refuse to fly because the idea and the subsequent invention are Western? Are we also to reject the global use of modern Western medicine because they may be incompatible with traditional observances in other cultures? For now, a contemplation of these questions will do. Perhaps, but the words of Lightfoot-Klein remain very instructive:

…childhood genital mutilations are anachronistic blood rituals inflicted on the helpless bodies of non-consenting children of both sexes. The reasons given for female circumcision in Africa and for the routine male cir. in the US are essentially the same. Both falsely touch the positive health benefits of the procedure. Both promise cleanliness and the absence of “bad” genital odours, as well as greater attractiveness and acceptability of the sex organs. The affected individuals in both cultures have come to view these procedures as something that was done for them and not to them.65

Female circumcision, like other habitually observed rituals in different societies and in different eras, must have a presumed social or religious relevance amongst its practitioners in order to remain serviceable. Once so convinced, it is hardly necessary to adduce further reasons for its observance, and the ritual would remain in practice until its usefulness is found wanting or alternate rituals with less inconveniences are introduced. In order to curb its practice, practitioners must be convinced that its assumed benefits can be achieved through other means impose with less severe hardship on beneficiaries. But given its long history in Africa this would require sustained effort in exposing its harmful effects to children and adults who are subjected to the procedure as a matter of course, and not by free will; and that a better policy would be to either abandon the practice altogether or retain it with the proviso that only individuals that have reached the age of consent may freely engage in it as an elective procedure. This is an area that would benefit from further research on alternative rituals that serve the same end.

References

1 Immigration And Naturalization Act. 1980. (8 U.S.C. sec. 1101 (a) (42) (A).

2 ibid.

3 IN RE KASINGA. 1996. Interim Decision 3278, 1996 Westlaw 379826, 35 ILM 1145

4 ibid. pp.5.

5 Lewis, Hope. 1995. Between Irua and Female Genital Mutilation: Feminist Human Rights Discourse and the Cultural Divide, 8 HARV. Hum. Rts. Journal, 1 2-3.

6 Larsen, Ulla; Yan, Sharon. 2000. Does Female Circumcision Affect Infertility and Fertility? A Study of the Central African Republic. Cote D’Ivoire, and Tanzania, Demography, Vol. 37, No. 3, 313-321

7 ibid.

8 WHO. 1996. Female Genital Mutilation: Report of a WHO Technical Working Group, Geneva.

9 Geertz, Clifford. 1973. Interpretation of Cultures, New York: Basic Books, pp. 5.

10 WHO. 1996. Female Genital Mutilation: Report of a WHO Technical Working Group, Geneva.

11 Rich, S., Joyce, S. 1997. Eradicating Female Genital Mutilation: Lessons for Donors. Occasional paper, Wallace Global Fund, Washington, D.C.

12 Boddy, Janice. 1989. Wombs and Alien Spirits. Madison Univ. of Wisconsin Press, pp. 52

13 Larsen, Ulla; Yan, Sharon. 2000. Does Female Circumcision Affect Infertility and Fertility? A Study of the Central African Republic. Cote D’Ivoire, and Tanzania, Demography, Vol. 37, No. 3, 313-321.

14ibid. at pp.316.

15 Boddy. 1989. pp. 54.

16 Geertz, 1973. pp.14.

17 ibid.

18 Gruenbaum, Ellen. 2000. The Female Circumcision Controversy: An Anthropological Perspective. University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 25.

19 Toubia, N; Rahman, A, 2000. A Guide to Laws and Policies Worldwide. Zed Book, New York. pp. 12.

20 ibid. at pp. 13.

21 Tobia, N. 1995. Female Genital Mutilation: A Call for Global Action. RAINBO, New York

22 Bashir, Layli. 1996. Female genital mutilation in the United States: An Examination of criminal and Asylum Law; The American University Journal of Gender & Law, 4 Am. U.J. Gender & Law, pp. 415.

23 Gruenbaum, 2000. pp. 35

24 ibid.

25 ibid. at pp. 153

26 ibid. at pp. 56.

27 ibid. at pp. 59.

28 ibid.

29 Boddy, 1989. pp. 56

30 Rich, S., Joyce, S. 1997. pp.38.

31 Universal declaration of Human Rights; G.A. res. 217A (III), UN Doc. A/810 at 71 (1948).

32 World health organization. 1979. Seminar on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women And Children, Khartoum, Sudan.

33 Assaad, Marie. 1980. Female Circumcision in Egypt: Social Implications, Current Research, and Prospects for Change. Studies in Family Planning, Vol. 11. No. 1, 3-16.

34 ibid.

35 Babalola, S., Adebayo, C. 1996. Evaluation Report of Female Circumcision Eradication Project in Nigeria, paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, New York

36 ibid.

37 United Nations General Assembly, Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (Geneva: U.N. General Assembly, A/RES/48/104, 23 Feb. 1994) at pp. 2.

38 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Art. 12, GA RES. 44/25, Annes, UN GAOR, 44th Sess., Supp. No. 49, at 199, UN Doc. A/44/49 (1989)

39 ibid. Art. No.24.

40 Freeman, Michael. 1994. The philosophical Foundations of Human Rights. Human Rights Quarterly, Aug., Vol. 16, n3, pp. 451-514.

41 Organization of African Unity. 1990. African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, Art. 24(3).

42 ibid. Art. No. 21(1).

43 United Nations (UN). 1994. Report on the International Conference on population and Development, New York.

44 WHO. 1996. Female Genital Mutilation: Report of a WHO Technical Working Group, Geneva.

45 Donnelly, Jack, 1989.Universal Human Rights in Theory and Practice; Cornell University Press, New York, P44.

46 ibid. at pp.120

47 Teson, F. 1984. International Human Rights and Cultural Relativism. Virginia Journal of International law, 25, pp. 87-122.

48 ibid. at pp. 13.

49 A. Belden Fields, and Wolf-Dieter Narr, 1992. Human Rights as a Holistic Concept; Human Rights Quarterly, Feb., Vol. 14, n1 p1-20.

50 Universal declaration of Human Rights, supra note 31.

51 Teson, F. 1984, supra note 47.

52 Donnelly, Kack, 1989, supra note 45.

53 Brown, Chris, 1993. Universal Human Rights: A Critique; in Dunne and Wheeler, Human Rights in Global Politics, pp. 105.

54 Howard, Rhoda, 1993. Cultural Absolutism and the Nostalgia for Community; Human Rights Quarterly, May, Vol. 15, n2 p315-338.

55 Assaad, Marie. 1980. Female Circumcision in Egypt: Social Implications, Current Research, and Prospects for Change. Studies in Family Planning, Vol. 11. No. 1, 3-16.

56 Babalola, S., Adebayo, C. 1996. supra note 35 at pp.21.

57 Steiner, H, and Alston, P, 2000. International Human Rights in Context; Oxford Univ. Press, pp.180.

58 ibid. at pp.189.

59 World Health Organization. 1998. Female Genital Mutilation: Report of a WHO Technical Working Group, Geneva

60 African Report, March, 2003, pp. 37.

61 ibid.

62 Donnelly, Jack, 1989, supra note 45.

63 ibid.

64 Lewis, Hope. 1995. Between Irua and Female Genital Mutilation: Feminist Human Rights Discourse and the Cultural Divide, 8 HARV. Hum. Rts. Journal, 1 2-3.

65 Lightfoot-Klein, H., 1989. Prisoners of Ritual: An Odyssey into female Genital Circumcision in Africa, Harrington Press, New York, pp. 78.

The 25% of 36 States And the FCT in Nigerian Constitution devolves to Simple Math

Prof. Mike A.A. Ozekhome removes doubt on what the Nigerian constitution requires for a presidential candidate to ascend to the highest political office in the country. We agree. Here is an excerpt of his analysis.

*By Prof. Mike A.A. Ozekhome, SAN, CON, OFR, FCIArb, LL.M, Ph.D., LL.D, D.Litt.*

My simple take on this is that when a debate on a serious controversial national issue gets to a crescendo such as we now have it, various dimensions of and opinions on the issue under discourse must be vigorously pursued, explored and interrogated. Consequently, as regards this raging ruckus and scrimmage as to whether the 25% votes required by S.134 (2)(b) of the 1999 Constitution ( as amended) is applicable to the FCT, Abuja, I have now decided to navigate further, some uncharted routes, by going mathematical to find X. This will surely emphasize to Ajulo, and others who hold similar or same views as his, that this matter is not just about to go away, or be buried, or swept under the mat, until it is, perhaps, finally laid to rest by the Supreme Court. Even at that, Scholars and Analysts will, for centuries to come, still interrogate it, in the same way, that the debate over the case of AWOLOWO V. SHAGARI & 2 Ors (1979) LPELR-653 (SC), still rages till date (44 years later!).

Contrary to the simplistic and cavalier manner with which Ajulo dismissed the 25% compulsory requirement (even while paradoxically also extensively discussing it himself), it will not vanish into thin air just like that! He gravely errs in thinking that the debate is simply about how to “interpret one of the simplest provisions in our Constitution”. We must tackle it headlong. Let us therefore now take the argument further. I have always believed that it is in the clash of ideas that the truth- the naked truth– finally emerges.

There is no doubt that the provisions of section 134(2)(b) of the Constitution is rooted in mathematics. It requires that a winning presidential candidate shall have “not less than one-quarter of the votes at the election in each of at least two-third of all the states in the Federation AND the Federal Capital Territory Abuja”. (Emphasis supplied).

As lawyers, we should not shy away from embarking on this mathematical pathway to resolve the steaming controversy. Yes, mathematics is part of lawyers’ job in resolving disputes; and Nigerian courts are not strangers to mathematical judgments. Afterall, the 1979 presidential election involving Shagari and Awolowo was wholly litigated, won and lost on the basis of the Supreme Court’s mathematical interpretation of what amounted then to 2/3 of the then 19 states of the Federation. The Supreme Court, in delivering judgment in favour of Shagari, ruled that the requirement of votes to win the Presidential election was 25% in 12 states, and no more. It cautiously avoided the attendant fractionalization of Kano State, so as to avoid absurdity in interpretation. My deep research has just thrown up a judgment where the court was called upon to interpret and translate 1.00 to percentage. The Honourable Justice Nelson Ogbuanya of the National Industrial Court, in resolving the mathematical legal question, held that “1.00 of an amount means one whole number and not a fraction; and when converted to percentage, it means 100% and not 1%”. See “https://guardian.ng/features” law Court rules that 1.00 base salary to mean 100% in mathematical judgment” – The Guardian 26th November, 2019).

Let me therefore state very clearly here, that contrary to what is being peddled by many commentators as purportedly settled judicial decisions on the status of FCT, Abuja (many of them critiquing my earlier write-up (see www.”ruebenabati.com.na-(opini

There is also no doubt that the FCT, Abuja, is not, strict sensu, a State (it has no State-like governance structure). However, by S.299 of the 1999 Constitution and many judicial decisions, it is “to be treated as a State“: See BABA-PANYA V. PRESIDENT FRN (2018) 15NWLR (Pt 1643)423; BAKAR V. OGUNDIPE (2021) 5 NWLR (Pt 1768) 9. A Community reading of section 2(2), 3(1)(4), 134(2)(b), 297, 298, 299, 301 and 302 of the 1999 Constitution shows that the FCT is accorded a special status as quite distinct from that of a normal state; notwithstanding that it is to be “treated as a state”.

In dealing with this my new vista which now takes on a mathematical dimension, there are agreed parameters to note and apply, as answering a mathematical question requires patiently adopting methodical approach, using certain laid down formula. This is what is called ‘operation show your work before putting QED on your answer’. The mathematical question thus posed by S.134 (2)(b) of the Constitution is this: what does it mean when it requires a winner of the presidential election to secure not less than (i.e at least) 1/4 ( 25%) of votes in each of at least 2/3 of all the states in the Federation (36 states) AND the FCT, Abuja? The first step is to note that there are two parts- the variable and constant figures. In mathematics, while constant is a fixed figure, variable figures are imprecise. But, the variables must, nonetheless be ascertained before proceeding to conclude or ascribe a fixed figure in a given arithmetical equation. It is this inability to ascertain the variable figure that usually makes some students afraid of, and intimidated by, mathematics. In the end, they always failed to find X (the constant), with the resultant hatred for mathematics. To find X, the variable figure must be worked out and ascertained in a fixed figure, such as the constant figure.

It is clear that while “2/3 of all the states in the Federation” is the variable figure, which if worked out would give 24 states and thus become a constant figure, the “FCT, Abuja”, is always the constant figure, which stands as 1. Working out the equation to show that the two parts (both variable and constant figures) are separate and distinct in their respective values must be applicable to the 25% votes requirement. This would be subjected to the BODMAS (Bracket, Order of power or roots, Division, Multiplication, Addition and Subtraction) Rule. This Rule is employed to explain the order of operation of mathematical expression. Here, Bracket plays the role of “AND”, which serves as coordinating conjunctive verb in English syntax, to ascertain the two parts separated by bracket: See BUHARI v. INEC (2008) 19NWLR (Pt 1120) 246 (for the definition “And”); and EYISI & ORS V. STATE (200) LPELR-1186 (SC) (for the definition of “Each”).

In applying this formulae:

The number of states =36;

2/3 of 36 as variable =24;

FCT, Abuja as constant =1

So, the 25% of 24 States AND FCT, Abuja (1), will be expressed as: 25 % (24)(1) in mathematics. This is interpreted in English as 25% of 24 and 1, but not 25. The 24 represents states, while 1 represents FCT, Abuja.

The intention of the lawmaker is quite clear here.

The FCT, Abuja, is the seat of power of the Nigerian leadership. It is a cosmopolitan convergence of all federating units of the nation. It is to be merely treated like a State; but not as a State for the strange purpose of counting the total number of States to become 37 instead of 36 States and the FCT, Abuja, as wrongly argued by some analysts. The FCT, Abuja, is the political nerve centre of Nigeria. It has been imbued with such a special status as a miniature Nigeria in such a way that any elected president must have to compulsorily win the required 25% vote in the FCT, Abuja, after winning 25% votes in 24 States.

The reasons for this are not far-fetched. FCT, Abuja, is the melting pot which unites all ethnic groups, tribes, religions, people of variegate backgrounds; and other distinct qualities and characteristics in our pluralistic society. It is indeed a multi-diverse and multi-faceted conglomerate of the different and distinct peoples of Nigeria, which according to Prof Onigu Otite, has about 474 ethnic groups which speak over 350 languages. The FCT, Abuja, is thus regarded as the “Centre of Unity”, which is a testament to its inclusiveness of all tribes, religions, ethnic groups, languages; and peoples of different backgrounds. Simply put, FCT, Abuja, is a territory or land mass that is made up of individuals from every State and virtually from all the Local Government Areas in the country. It is itself made up of 6 Area Councils, quite distinct from the 768 LGAs in Nigeria, thus bringing the total to 774 LGCs in Nigeria. Consequently, scoring 25% of votes cast in the FCT, Abuja, is a Presidential candidate’s testament to being widely accepted by majority of the Nigerian people. The President is not expected to be a tenant in his seat of power. Will he pay rent to the 24 states he scored 25% votes? I do not know. Or, do you?

The framers of the 1999 Constitution certainly desired for Nigeria, a President that is widely accepted, with national spread; and not one that is a regional kingpin with support only from of his tribe, region, or ethnic group. The provisions contained in section 134 of the 1999 Constitution are meant to reflect this. In the same vein, the framers of the 1999 Constitution viewed the FCT, Abuja, as a melting pot; a sort of mini-Nigeria. Thus, like a commentator aptly posited, the position or status of the FCT, Abuja, assumes that of a COMPULSORY question that a presidential candidate must ANSWER in the electoral examination. With the FCT, Abuja, serving as the seat of the Federal Government-with all ministries and MDAs situated in it – it represents a Dolly Parton’s “Coat of many colours”. This is why the Federal Character provided for in sections 14(3),(4); 153(1); and 318(1) of the 1999 Constitution is also reflected in the administration of FCT, even though the Gbagyis are the original Aborigines of the FCT.

The only logical conclusion that can be drawn from the above is that sections 134 (2)(b) and 299 are not mutually exclusive or contradictory, as some commentators posit. Rather, section 299 actually supports and complements section 134.

Whether FCT, Abuja, is regarded as a super-state, full State, pseudo-State, quasi-State, or semi-State, is to me, immaterial. Even if it is none of these, what matters is the clear intention of the Constitution-makers.

Had the law makers intended that the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, will be treated simply as a “State” and no more in section 134(2)(b) of the Constitution, they would have simply stopped there. There was no need to specifically add the new phrase, “AND the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja”, as in section 134(2)(b). The Constitution would simply have provided for “two-thirds of all the States in the Federation”, and stopped there. But, it did not.

From a historical perspective (I am a student of history), recall that the AWOLOWO V. SHAGARI case and section 299 of the 1999 Constitution which states that its provisions shall apply to the FCT, Abuja, “as if it were one of the states of the Federation; including the BABA PANYA and BAKARI cases (supra), often cited with éclat, but out of context, did not deal with the issue of elections, or what percentage of the votes was expected of a presidential candidate. They merely dealt with the issues that were presented in those cases. No more. It is trite law that a case is only an authority for what its peculiar facts present: BABATUNDE v. PASTA (2007) 13 NWLR pt. 1050 pg. 113 @ 157; ADEGOKE MOTORS v. ADESANYA (1989) 3 NWLR (pt. 109) pg. 250; UWUA UDO v. THE STATE SC. 511/2014; SKYE BANK PLC. & ANOR. V. CHIEF MOSES BOLANLE AKINPEJU (2010) 9 NWLR (Pt LL98) 179; OKAFOR V. NNAIFE (1987) 4 NWLR (Pt 64)129; PDP V. INEC & ORS (2018) LPELR-44373(SC); LAGOS STATE GOVT. & ORS V. ABDULKAREEM & ORS (2022) LPELR-58517 (SC); ILA ENTERPRISES LTD & ANOR V. UMAR ALI & CO. NIG LTD (2022) LPELR-75806 (SC).

For example, when section 48 of the 1999 Constitution provides that the “Senate shall consist of three Senators from each state AND one from the FCT, Abuja”, why didn’t these canvassers of FCT, Abuja, being merely a state, argue that once we have three Senators from “each state”, we should discard the “AND” which gives one Senator to the FCT, Abuja, and thus deprive the FCT, Abuja, of its Senator? This provision is one amongst several others which shows that the FCT, Abuja, is to be treated distinctly and separately from the other 24 states. There is no ambiguity in section 134(2)(b) such as to bring in aid, existing canons of statutory interpretation, such as the “Golden Rule”, “Mischief Rule”, etc. It is axiomatic that all sections of the Constitution must be wholly and holistically construed together so as to avoid leaving out some portions, or rendering them nugatory. See THE ESTATE OF ALHAJI N.B. SOULE v. OLUSEYE JOHNSON & CO & ANOR (1974) LPELR-3169 (SC). The reason is that law makers are presumed not to use superfluous, otiose or extravagant words in provisions of the Constitution or statutes which they make.

CONCLUSION

It is my considered opinion that the scope of consideration of the FCT, Abuja, as a State, only applies to the enjoyment and vesting of executive, legislative and judicial powers by relevant bodies in the FCT. It does not apply to all matters, extents, and for all purposes. Further, an interpretation that Section 299 of the Constitution applies for all purposes is too narrow. It is not holistic or inclusive. It will render many other parts of the Constitution redundant, futile, unproductive, meaningless and therefore, unnecessary. Certainly, such could not have been the intention of the Legislature or law makers.

Section 134(2) of the Constitution must therefore be interpreted to mean that for a candidate to win the Presidential election, such a candidate must obtain 25% of the votes cast in two-thirds of all the States in the Federation (24 States); AND further, in the FCT, Abuja. This is a compulsory requirement for a valid return as President. It seems to me that INEC was not properly legally guided when it declared a President-elect. The Nichodemus announcement and declaration was obviously too hasty, premature and rash.

A great writer (Onwa Nnobi) was most apt when he stated:

“If 5 credits AND English Language are prerequisite to gaining admission into a higher school of Learning; and you make 10As in 10 subjects, but get F9 in English Language, does it qualify you for admission? It is not just commonsense and logic. It is incontrovertible”. I cannot give a better example. But, let me try two more examples of mine:

If I request to see 24 Corpers in my law firm AND OKON, it means I want to see 25 persons in all; but Okon must be one of the 25 persons. So if 24 or 25 persons in my law firm show up, without Okon, have I had all the persons I wanted to see? The answer is NO. To satisfy my request, Okon must show up in addition to the 24, thus making the 25 persons I desire to see. Okon is a Constant; 24 Corpers is a variable. The variables must be worked by BODMAS-Rule to find the constant.

As a second example, if I tell my dear wife to treat Andrew (my ward living with us) “like my son”, does that really make Andrew my biological son? I think not. Let me end this piece in response to Ajulo’s apophthegym of the “unwrinkled face (which) is not good for a resounding slap” with some words of advice.

Ajulo ought to know, from the deep recesses of his conscience and inner mind that what we witnessed on 25th February, 2023, was not democracy in practice. Abraham Lincoln, who made his famous Gettysburg speech on 19th November, 1863, had described democracy as government of the people, for the people and by the people. He must be turning in his centuries-old grave. The last election was nothing but a sham and shambolic election of “first-kill-maim-allocate-thum

The new refrain in town has since become “GO TO COURT”; an obvious addition to our warped political lexicon. The election in my humble view, was the shame of a country that has been held down for decades by the jugular by insensitive and insensate elite state captors. It was a purported election in which a supposed Nigerian president-elect allegedly scored 8,795,721 (only about 9.409% of the registered 93.40 million voters). And WITHOUT THE FCT, Abuja! So, that means less than 3.998% of the entire population of the Nigerian people comprising of 220.075.973 million people as at 27th March, 2023- the very people he seeks to govern! That is a mere 454,163 votes more than Chief Abiola’s votes scored about 30 years ago, when Nigeria’s population was only 102.8 million people. It was virtually half of President Buhari’s 15,191,847 votes in 2019; and even far less than the votes of the then runner-up, Atiku Abubakar, which was 11,262,928. What an election!

Rise of the youths; a battle for the heart and soul of Nigeria has been joined

John O. Ifediora @ifediora_john.

All political dynasties eventually fail, but their demise come much quicker if the reasons for their being are no longer in consonant with extant social sensibilities of the electorate. The histories of nation-states are replete with the natural death of moribund political institutions too feckless and spent to serve the needs of a progressively sophisticated citizenry. The two major parties in Nigeria, APC and PDP, a political duopoly that interchangeably misruled the affairs of Nigerians beginning in 1999, are now forced to take stock of what they have done to and for the country, but more importantly to give a clear narrative of their administrative agenda in the last twenty-four years. The record is one of abysmal and catastrophic failures that came to a head in the last presidential election held on February 25, 2023; the youths, whose current and future prospects have been mortgaged by the political elites that ruled the country, have risen to demand a course correction, and re-energized the Labour Party that represents their vision for Nigeria…one of clean and efficient government that puts the interests of the nation above the cult of personality and special interests. It is a struggle that favors them because all the relevant socio-economic variables are perfectly aligned against the old guards.

The first shot across the bow was delivered by the flag bearer of the Labour Party, Mr. Obi, on March 2, 2023 in a petition filed against INEC with the Presidential Electoral Petition Court in Abuja to compel production of documents that informed the decision to call the election results in favor of Bola Tinubu, the APC presidential candidate. The legal papers filed read in part: “Motion Ex Parte brought pursuant to Section 36(1) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria,1999, Section 146 of the Electoral Act, 2002 and Paragraphs 47(1) 54 of the First Schedule to the Electoral Act, 2002 and under the inherent power of the honourable tribunal.”

The election has been widely criticized by various international and domestic bodies as below acceptable standards of electoral process and plagued by violence and voter suppression. The final vote tally, not surprisingly, reflected a seriously flawed and compromised norm for a free and fair exercise of participatory democracy; voters in various parts of the country were denied access to polling stations and many were subjected to psychological intimidation and physical violence. The youths who had worked for months to place the country on a new path completely devoid of the status quo that served average Nigerians a steady dose of malfeasance and crippling bureaucratic corruption saw this as further justification to jettison a system that has perennially failed them.

The outcome of the presidential election, while disappointing to many, has provided the youths an important opportunity to strengthen the reach and depth of the Labour Party through grassroots political activism. As the party chieftains pressed their case in the courts, party operatives are busily getting candidates of the Labour Party elected to the federal house of representatives and governors' mansions, thus creating an electoral architecture that was lacking a few months ago but necessary to create a viable political party. By patiently implementing this two-pronged approach, the youths are effectively adopting a long-run strategy that would keep their party of choice in power as soon as the next presidential election. Through sustained litigations in the courts, the Labour Party effectively keeps the ruling party perpetually on the defensive and minimize opportunities for venality and corrupt practices. This much is the perceived strategy of the Labour Party, and if properly executed it may yield the outcome the youths of Nigeria had hoped for in the first instance. If not, then the country should brace itself for a protracted existential struggle between the old guards of Nigeria’s political elites and its numerically superior and digitally plugged-in youths.

As the struggle unfolds in the courts and in the political arena, it is instructive to keep these statistics in perspective:

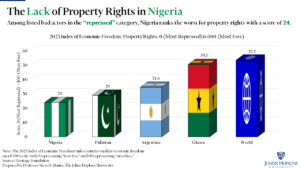

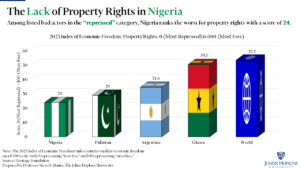

- Under the leadership of President Buhari and the governing party of APC, Nigeria now ranks in the lowest percentile for property rights in the world as reported by the Index of Economic Freedom.

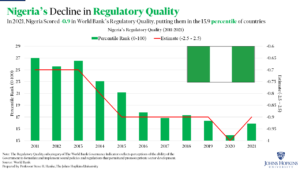

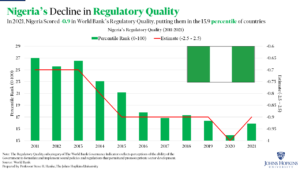

2. In the World Bank’s ranking of nations in its Regulatory Quality Index, Nigeria’s score of -0.9 in 2021 represents a decline by 11% from its score in 2011.

Both scores are indicative of a failed state and would make getting international loans for infrastructure development from international institutions much harder and expensive. These vectors are not encouraging.

*photo courtesy: Johns Hopkins University, The World Bank, Getty images.

Rise of the youths; a battle for the Heart and Soul of Nigeria has been joined

John O. Ifediora @ifediora_john

All political dynasties eventually fail, but their demise come much quicker if the reasons for their being are no longer in consonant with extant social sensibilities of the electorate. The histories of nation-states are replete with the natural death of moribund political institutions too feckless and spent to serve the needs of a progressively sophisticated citizenry. The two major parties in Nigeria, APC and PDP, a political duopoly that interchangeably misruled the affairs of Nigerians beginning in 1999, are now forced to take stock of what they have done to and for the country, but more importantly to give a clear narrative of their administrative agenda in the last twenty-four years. The record is one of abysmal and catastrophic failures that came to a head in the last presidential election held on February 25, 2023; the youths, whose current and future prospects have been mortgaged by the political elites that ruled the country, have risen to demand a course correction, and re-energized the Labour Party that represents their vision for Nigeria…one of clean and efficient government that puts the interests of the nation above the cult of personality and special interests. It is a struggle that favors them because all the relevant socio-economic variables are perfectly aligned against the old guards.

The first shot across the bow was delivered by the flag bearer of the Labour Party, Mr. Obi, on March 2, 2023 in a petition filed against INEC with the Presidential Electoral Petition Court in Abuja to compel production of documents that informed the decision to call the election results in favor of Bola Tinubu, the APC presidential candidate. The legal papers filed read in part: “Motion Ex Parte brought pursuant to Section 36(1) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria,1999, Section 146 of the Electoral Act, 2002 and Paragraphs 47(1) 54 of the First Schedule to the Electoral Act, 2002 and under the inherent power of the honourable tribunal.”

The election has been widely criticized by various international and domestic bodies as below acceptable standards of electoral process and plagued by violence and voter suppression. The final vote tally, not surprisingly, reflected a seriously flawed and compromised norm for a free and fair exercise of participatory democracy; voters in various parts of the country were denied access to polling stations and many were subjected to psychological intimidation and physical violence. The youths who had worked for months to place the country on a new path completely devoid of the status quo that served average Nigerians a steady dose of malfeasance and crippling bureaucratic corruption saw this as further justification to jettison a system that has perennially failed them.

The outcome of the presidential election, while disappointing to many, has provided the youths an important opportunity to strengthen the reach and depth of the Labour Party through grassroots political activism. As the party chieftains pressed their case in the courts, party operatives are busily getting candidates of the Labour Party elected to the federal house of representatives and governors' mansions, thus creating an electoral architecture that was lacking a few months ago but necessary to create a viable political party. By patiently implementing this two-pronged approach, the youths are effectively adopting a long-run strategy that would keep their party of choice in power as soon as the next presidential election. Through sustained litigations in the courts, the Labour Party effectively keeps the ruling party perpetually on the defensive and minimize opportunities for venality and corrupt practices. This much is the perceived strategy of the Labour Party, and if properly executed it may yield the outcome the youths of Nigeria had hoped for in the first instance. If not, then the country should brace itself for a protracted existential struggle between the old guards of Nigeria’s political elites and its numerically superior and digitally plugged-in youths.

As the struggle unfolds in the courts and in the political arena, it is instructive to keep these statistics in perspective:

- Under the leadership of President Buhari and the governing party of APC, Nigeria now ranks in the lowest percentile for property rights in the world as reported by the Index of Economic Freedom.

2. In the World Bank’s ranking of nations in its Regulatory Quality Index, Nigeria’s score of -0.9 in 2021 represents a decline by 11% from its score in 2011.

Both scores are indicative of a failed state and would make getting international loans for infrastructure development from international institutions much harder and expensive. These vectors are not encouraging.

*photo courtesy: Johns Hopkins University, The World Bank, Getty images.

Nigeria’s pregnancy has a due date of February 25; what it delivers will either be a new nation or a re-incarnation of itself.

Editorial commentary @Ifediora_john

February 25, 2023 marks a fork in the road for Nigeria and its inhabitants of unknown number…the boarders are too porous for an informed estimation or reasoned statistical extrapolation. But by all accounts, it is a large number, and collectively operates the largest market for consumer goods in Africa and exports a significant fraction of fossil fuels that drive the global economy. These alone give Nigeria a global presence, hence what it does matters. But the country’s history of unrealized potential and a battered global image of its citizens have not been salutary to economic development and have progressively gotten worse as the country swaps one rotten leadership for another. A list of the ills that have defined the lived experiences of Nigerians beginning in the early 1980s is a matter of record and need not be recounted here, but one thing stands out in the current effort to decide who would lead Nigerians in the next four years … this plebiscite will be largely defined by the young who are now compelled and energized to re-define their future prospects, their global image, and that of Nigeria.

Nigeria’s young are more populous than the old and aged, they consume more education than the preceding generation, they possess more technical skill sets and are by far better integrated into the global space than all their predecessors combined. That they have risen to demand a severance of the umbilical cord that links them to their unpleasant and shameful past is a most meaningful course-correction imperative to date that is at once aesthetically pleasing and yet prepotent. In the midst of powerful voices advocating the status quo of patronage politics, the vast majority of young voters identify with the message and a break from the past advanced by Mr. Peter Obi, the presidential candidate of the Labor Party. That he is young, speaks their language of clean government, frugal by temperament, and boasts a record of administrative sagacity endear him to the young and the old alike eager for a change. It would be a shame to disappoint them.

The decision to deliver a new nation is now squarely in the hands of Nigeria’s young; the old and the aged cannot be relied upon entirely to break from the past and may indeed be obliged to stay the course by habitual instincts informed by pecuniary gratification. Patronage politics is well and alive in Nigeria, and may very well deliver the country, once again, to the county’s political gangsters. This too, will be shameful.

The US returns to Nigeria $954,000 laundered by Governor Alamieyeseigha

Abuja, Nigeria.

In a press brief on February 16, 2023 the United States’ ambassador to Nigeria, Mary Beth Leonard, announced the return of $954,000 to the Nigerian government as proceeds from laundered financial assets seized from former governor of Bayelsa State, Diepreye Alamieyeseigha. In the press brief, Ambassador Leonard states:

“….the official salary of the former governor during his tenure as a public servant from 1999 to his impeachment in 2005 did not match the said amount. However, during that time, he accumulated millions of dollars through abuse of office, and money laundering.”

The US government, in line with President Biden’s policy on Africa, has stepped up anti-corruption measures by way of asset seizure and forfeiture. Assets illegally purchased in the US by corrupt African officials are now being confiscated and liquidated, and the proceeds returned to the country of origin. The UK has been a leading force in this regard for over a decade. The problem now is that when the proceeds are returned they find their way back into private accounts in Western banks.

President Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria immediately directed that the returned funds be returned to Bayelsa State to help strengthen the healthcare sector.

Nigerians head to the polls this month to elect a new president, this time a nasal test maybe their best guide

Editorial Commentary.

To state that Nigerians are resilient and resourceful would be a grand understatement, for both adjectives fail to capture the enviable depth and breadth of brilliancy that define their collective lot (What they have done with this attribute on the international scene is a different consideration). Equally enviable is the variety of natural resources nature has endowed the geographic and territorial competence they claim and occupy. But this is where a generous description ends, and a nightmarish tale becomes the appropriate literature genre to effectively narrate the current state of affairs of the average Nigerian. By all reasonable expectations, Nigerians should by now have at their disposal the various social amenities that commonly define advanced economies…an economy that furnishes good employment opportunities, reasonably safe cities and towns, a functional healthcare sector, good network of roads, steady-state electricity, a good educational system, affordable housing, and more. The country has within it and outside its shores the requisite human capital to industrialize its economy and manage a sustainable trajectory of growth that would afford its citizens these amenities with relative ease. Reasons for the catastrophic failure to achieve this expectation are too numerous to adumbrate here but chief amongst them is the bad choice of leadership the electorate has consistently made or imposed on them over the past decades. This is unfortunate, but the electorate now has an opportunity afforded by this election to make a course-correction that would ultimately define Nigeria’s future as a viable nation-state or default to one of confederacy with independent nations loosely connected by jointly held infrastructures and assets.

In the normal run of things, making the right choice of leadership in national elections is a difficult one, and once again, Nigerians have managed to present to the electorate three presidential candidates each as unappealing as the other but for different reasons. As the cacophony of unreasoned pronouncements from the candidates and their campaign staff daily assault the auditory and optical senses of the electorate, a reasoned certainty is that one of the candidates would be elected president of the country. This choice would be made from an assortment of polished curriculum vitae of the candidates (as most CVs tend to be), unverifiable claims of capabilities, actual resumes that would impress the most unrepentant money launderers, and acts of bureaucratic corruption that would make their predecessors cringe with affectations of modesty. At least one of these attributes applies to one of the candidates, and all apply to two. The options are rotten but left with a Hobson’s Choice of ‘choose one or none,’ the electors would go to the polls armed with the sensitivity of their nostrils and choose the least pungent. We turn now to specificities.