Nigeria at cross-roads: Completely lost but making good progress

Editorial commentary.

Like all nation-states before it, Nigeria is now confronted with stark existential choices --- stay the current course of self-delusion or boldly grapple with deep-seated unresolved issues that threaten to disintegrate it. The idea of a unitary Nigeria is appealing, but it requires extraordinary self-less effort and sacrifices that both its people and leadership are unwilling or capable of rendering. It may very well be that the opportunities it had for course-correction to keep it whole are no longer available. An October 23rd article on Nigeria by the Economist, as presented below, is instructive.

Africa’s biggest nation faces its biggest test since its civil war 50 years ago

The Economist. October 23rd, 2021.

Little more than six decades ago, as Nigeria was nearing independence, even those who were soon to govern Africa’s largest country had their doubts about whether it would hold together. British colonists had drawn a border around land that was home to more than 250 ethnic groups. Obafemi Awolowo, a politician of that era, evoked Metternich, fretting that “Nigeria is not a nation. It is a mere geographical expression.”

The early years of independence seemed to prove him right. Coup followed coup. Ethnic pogroms helped spark a civil war that cost 1m lives, as the south-eastern region calling itself Biafra tried to break away and was ruthlessly crushed. Military rule was the norm until 1999. Despite this inauspicious start, Nigeria is now a powerhouse. Home to one in six sub-Saharan Africans, it is the continent’s most boisterous democracy. Its economy, the largest, generates a quarter of Africa’s gdp. Nollywood makes more titles than any other country’s film industry bar Bollywood. Three of sub-Saharan Africa’s four fintech “unicorns” (startups valued at more than $1bn) are Nigerian.

Why, then, do most young Nigerians want to emigrate? One reason is that they are scared. Jihadists are carving out a caliphate in the north-east; gangs of kidnappers are terrorising the north-west; the fire of Biafran secessionism has been rekindled in the oil-rich south-east. The violence threatens not just Nigeria’s 200m people, but also the stability of the entire region that surrounds them.

Readers who do not follow Nigeria closely may ask: what’s new? Nigeria has been corrupt and turbulent for decades. What has changed of late, though, is that jihadism, organised crime and political violence have grown so intense and widespread that most of the country is sliding towards ungovernability. In the first nine months of 2021 almost 8,000 people were directly killed in various conflicts. Hundreds of thousands more have perished because of hunger and disease caused by fighting. More than 2m have fled their homes.

The jihadist threat in the north-east has metastasised. A few years ago, an area the size of Belgium was controlled by Boko Haram, a group of zealots notorious for enslaving young girls. Now, Boko Haram is being supplanted by an affiliate of Islamic State that is equally brutal but more competent, and so a bigger danger to Nigeria. In the south-east, demagogues are stirring up ethnic grievances and feeding the delusion that one group, the Igbos, can walk off with all the country’s oil, the source of about half of government revenues. President Muhammadu Buhari has hinted that Biafran separatism will be dealt with as ruthlessly now as it was half a century ago.

Meanwhile, across wide swathes of Nigeria, a collapse in security and state authority has allowed criminal gangs to run wild. In the first nine months of this year some 2,200 people were kidnapped for ransom, more than double the roughly 1,000 abducted in 2020. Perhaps a million children are missing school for fear that they will be snatched.

Two factors help explain Nigeria’s increasing instability: a sick economy and a bumbling government. Slow growth and two recessions have made Nigerians poorer, on average, each year since oil prices fell in 2015. Before covid-19, fully 40% of them were below Nigeria’s extremely low poverty line of about $1 a day. If Nigeria’s 36 states were stand-alone countries, more than one-third would be categorised by the World Bank as “low-income” (less than $1,045 a head). Poverty combined with stagnation tends to increase the risk of civil conflict.

Economic troubles are compounded by a government that is inept and heavy-handed. Mr Buhari, who was elected in 2015, turned an oil shock into a recession by propping up the naira and barring many imports in the hope this would spur domestic production. Instead he sent annual food inflation soaring above 20%. He has failed to curb corruption, which breeds resentment. Many Nigerians are furious that they see so little benefit from the country’s billions of petrodollars, much of which their rulers have squandered or stolen. Many politicians blame rival ethnic or religious groups, claiming they have taken more than their fair share. This wins votes, but makes Nigeria a tinderbox.

When violence erupts, the government does nothing or cracks heads almost indiscriminately. Nigeria’s army is mighty on paper. But many of its soldiers are “ghosts” who exist only on the payroll, and much of its equipment is stolen and sold to insurgents. The army is also stretched thin, having been deployed to all of Nigeria’s states. The police are understaffed, demoralised and poorly trained. Many supplement their low pay by robbing the public they have sworn to protect.

To stop the slide towards lawlessness, Nigeria’s government should make its own forces obey the law. Soldiers and police who murder or torture should be prosecuted. That no one has been held accountable for the slaughter of perhaps 15 peaceful demonstrators against police abuses in Lagos last year is a scandal. The secret police should stop ignoring court orders to release people who are being held illegally. This would not just be morally right, but also practical: young men who see or experience state brutality are more likely to join extremist groups.

Things don’t have to fall apart

Second, Nigeria needs to beef up its police. Niger state, for instance, has just 4,000 officers to protect 24m people. Local cops would be better at stopping kidnappings and solving crimes than the current federal force, which is often sent charging from one trouble spot to another. Money could come from cutting wasteful spending by the armed forces on jet fighters, which are not much use for guarding schools. Britain and America, which help train Nigeria’s army, could also train detectives. Better policing could let the army withdraw from areas where it is pouring fuel on secessionist fires.

The biggest barrier to restoring security is not a lack of ideas, nor of resources. It is the complacency of Nigeria’s cosseted political elite—safe in their guarded compounds and the well-defended capital. Without urgent action, Nigeria may slip into a downward spiral from which it will struggle to emerge.

The African Genome Project...Where Human Life Began

*Article credit.

WHEN THE Mutambaras’ first son was a about 18 months old they began to worry about his hearing. The toddler did not respond when asked to “come to Mama”. He was soon diagnosed as deaf, though no doctor could tell the Zimbabwean couple the cause. Several years later their second son was also born deaf.

This time a doctor referred them to Hearing Impairment Genetics Studies in Africa (hi-genes), set up in 2018 by Ambroise Wonkam, a Cameroonian professor of genetics now at the University of Cape Town. The project is sequencing the genomes of Africans with hearing loss in seven countries to learn why six babies in every 1,000 are born deaf in Africa, a rate six times that in America. In Cape Town, where Mr and Mrs Mutambara (not their real names) live, a counsellor explained that the boys’ deafness is caused by genetic variants rarely found outside Africa.

What is true of deafness is true of other conditions. The 3bn pairs of nucleotide bases that make up human dna were first fully mapped in 2003 by the Human Genome Project. Since then scientists have made publicly available the sequencing of around 1m genomes as part of an effort to refine the “reference genome”, a blueprint used by researchers. But less than 2% of all sequenced genomes are African, though Africans are 17% of the world’s population (see chart). “We must fill the gap,” argues Dr Wonkam, who has proposed an initiative to do just that—Three Million African Genomes (3mag).

The evolutionary line leading to Homo sapiens diverged 5m-6m years ago from that leading to chimpanzees, and for almost all that time the ancestors of modern humans lived in Africa.

Only about 60,000 years ago did Homo sapiens venture widely beyond the continent, in small bands of adventurers. Most of humanity’s genetic diversity, under-sampled though it is, is therefore found in Africa. Unfortunately, that diversity is also reflected in the greater variety of genetic illnesses found there.

The bias in sequencing leads to under-diagnosis of diseases in people of (relatively recent) African descent. Genetic causes of heart failure, such as the one that caused the ultimately fatal collapse of Marc-Vivien Foé, a Cameroonian football player, during a game in 2003, are poorly understood. The variation present in most non-Africans with cystic fibrosis is responsible for only about 30% of cases in people of African origin. This is one reason, along with its relative rarity, that the illness is often missed in black children. Standard genetic tests for hearing loss would not have picked up the Mutambara boys’ variations. And such is the diversity within the continent that tests in some countries would be irrelevant in others. In Ghana hi-genes found one mutation responsible for 40% of inherited deafness. The same variation has not been found in South Africa.

Bias also means that little is known about how variations elsewhere in the genome modify conditions. With sickle-cell disease, red blood cells look like bananas rather than, as is normal, round cushions. About 75% of the 300,000 babies born every year with sickle-cell disease are African. The high share reflects a bittersweet twist in the evolutionary tale; sickle-cell genes can confer a degree of protection against malaria. Other mutations are known to lessen sickle-cell’s impact, but most knowledge of genetic modifiers is particular to Europeans.

Quicker and more accurate diagnosis would mean better treatment. The sooner parents know their children are deaf, the sooner they can begin sign language. Algorithms that incorporate genetic information, such as one for measuring doses of warfarin, a blood-thinner, are often inappropriately calibrated for Africans.

Knowing more about Africans’ genomes will benefit the whole world. The continent’s genetic diversity makes it easier to find rare causes of common diseases. Last year researchers investigating schizophrenia sequenced the genomes of about 900 Xhosas (a South African ethnic group) with the psychiatric disorder. They found some of the same mutations that a team had discovered in Swedes four years earlier. But those researchers had to analyse four times as many of the homogeneous Scandinavians to find it. Research by Olufunmilayo Olopade, a Nigerian-born oncologist, into why breast cancer is relatively common in Nigerian women, has revealed broad insights into tumour growth.

Dr Wonkam’s vision for 3mag, as outlined in Nature, a scientific journal, is for 300,000 African genomes to be sequenced per year over a decade. That is the minimum needed to capture the continent’s diversity. He notes that the uk biobank is sequencing 500,000 genomes, though Britain’s population is a twentieth the size of Africa’s. The plummeting cost of technology makes 3mag possible. Sequencing the first genome cost $300m; today the cost of sequencing is around $1,000. If data from people of African descent in similar projects, like the uk biobank, were shared with 3mag, that would help. So too would collaboration with genetics firms, such as 54Gene, a Nigerian start-up.

The 3mag project is building on firm foundations. Over the past decade the Human Heredity and Health in Africa consortium, sponsored by America’s National Institutes of Health and the Wellcome Trust, a British charity, has supported research institutes in 30 African countries. It has funded local laboratories for world-class scientists such as Dr Wonkam and Christian Happi, a Nigerian geneticist.

There are practical issues to iron out. One is figuring out how to store the vast amounts of data. Another is rules around consent and data use, especially if 3mag will involve firms understandably keen to commercialise the findings. Dr Wonkam wants to see an ethics committee set up to review this and other matters.

At times he has wondered whether his plan is “too big, too crazy and too expensive”. But similar things were said about the Human Genome Project. Its researchers used the Rosetta Stone as a metaphor for the initiative and its ambition. In a subtle nod, Dr Wonkam has a miniature of the obelisk on a shelf in his office. It is also a reminder of how understanding African languages, whether spoken or genetic, can enlighten all of humanity.

*The Economist.

Reverse Migration to Africa ...Policy Makers Should Encourage this Spectacle.

*Article credit.

WHEN BANKS started to fail and protesters began filling the streets in 2019, Moussa Khoury resisted the temptation to leave his native Lebanon. After a massive explosion flattened part of Beirut, the capital, last year, he fixed his broken windows and stayed put. But in the end he could not withstand the collapse of Lebanon’s currency. Mr Khoury runs a startup selling vegetables grown in hydroponic planters. His customers paid him in liras, while his suppliers demanded hard currency. So in April he accepted an offer from an acquaintance who promised to invest in the business—if Mr Khoury moved it to Ghana.

More than 250,000 Lebanese probably live in west Africa. It is impossible to know how many have moved there since Lebanon’s economic crisis began in 2019, but the evidence suggests the number is large. A pilot of Lebanese descent living in Togo says Lebanese pack his flights to west Africa. Lebanon’s embassy in Nigeria reports a “noticeable increase” in Lebanese moving to the country. Guita Hourani, who leads a centre that studies migration at Notre Dame University-Louaize in Lebanon, says her office is flooded with calls from locals who want advice on how to track down relatives abroad, including in Africa.

Many Lebanese came to west Africa in the 19th century, disembarking (some say by mistake) from ships heading for America. The new arrivals proved remarkably successful, first as middlemen between locals and colonising powers, later as business owners and commodity traders. Today, for example, Lebanese reportedly control many of the companies in Ivory Coast that handle exports of coffee or cocoa.

Over a century of conflict, crisis and famine have scattered Lebanese all over the world. But these days Lebanese find it much easier to obtain visas from west African destinations than from America or European countries. Jobs are easier to get hold of, too. Someone always knows someone who has an opening, says Karim Maky, a Senegalese of Lebanese descent. Skilled workers are paid well. And most west African countries already have Lebanese churches, mosques and schools.

Some newcomers plan to stay for a while. Take Ibrahim Chahine, a young mechanical engineer who left Lebanon last year. Canada’s visa process was too cumbersome, he says. His applications to Gulf countries went unanswered. So when he got a job at a company run by Lebanese in Nigeria, he didn’t think twice. Within two weeks he had moved to Abuja, the capital. He expects to stay for ten years.

Mr Khoury is not so sure. He had hoped to use his startup to boost agricultural production in Lebanon, which currently imports nearly all of its food. Instead he is building a greenhouse in Accra, the capital of Ghana, with the aim of selling baskets of kale, leeks and lettuce to local supermarkets, restaurants and hotels. He plans to spend at least a year there. But his extended family is back in Lebanon. And he’s kept his operation there open. That’s because of nostalgia, he says, not profits.

*The Economist.

International Human Rights Law and Practice

By Illias Bantekas and Lutz Oette.

This unique textbook merges human rights law with its practice, from the courtroom to the battlefield. Human rights are analysed in their particular context, and the authors assess, among other things, the impact of international finance, the role of NGOs, and the protection of rights in times of emergency, including the challenges posed by counter-terrorism. In parallel, a series of interviews with practitioners, case studies and practical applications offer multiple perspectives and challenging questions on the effective implementation of human rights. Although the book comprehensively covers the traditional areas of international human rights law, including its regional and international legal and institutional framework, it also encompasses, through distinct chapters or large sections, areas that have a profound impact on human rights worldwide, such as women's rights, human rights and globalisation, refugees and migration, human rights obligations of non-state actors, debt and human rights, and others.

Hidden Toll of COVID in Africa Threatens Global Pandemic Progress

Sarah Wild.

Undercounting or ignoring cases of the disease on the continent could lead to new variants that might derail efforts to end the pandemic. Kenya and other African countries are reporting relatively few COVID cases, but studies suggest that the continent’s true burden of disease may be undercounted.

Africa has suffered about three million COVID-19 cases since the start of the pandemic—at least officially. The continent’s comparatively low number of reported cases has puzzled scientists and prompted many theories about its exceptionalism, from its young population to its countries’ rapid and aggressive lockdowns.

But numerous seroprevalence surveys, which use blood tests to identify whether people have antibodies from prior infection with the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), point to a significant underestimation of African countries’ COVID burden. Undercounting could increase the risk of the disease spreading widely, hinder vaccine rollout and uptake, and ultimately threaten global efforts to control the pandemic, experts warn. Wherever the virus is circulating—especially in regions with little access to vaccines—new mutations are likely to arise, and it is crucial to identify them quickly.

Viral variants are already complicating vaccination drives around the world. New SARS-CoV-2 variants first detected in South Africa, Brazil and the U.K. have raised concerns that they could be more transmissible or make available vaccines less effective. And drugmakers are scrambling to develop vaccine boosters to protect against them. (The currently authorized vaccines still provide strong protection against severe disease and death.)

Undiagnosed transmission of COVID in African countries increases the risk of new variants taking hold in the population before authorities have a chance to detect them and prevent their spread, says Richard Lessells, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the KwaZulu-Natal Research and Innovation Sequencing Platform in South Africa. That nation has the highest number of recorded cases on the continent (many of them caused by a new variant). And officials suspect that its surveillance network is only catching one in every 10 infections.

Mutations develop spontaneously as a virus replicates and spreads. While many of them are innocuous, they can sometimes make the pathogen more transmissible or deadly, as seen in the SARS-CoV-2 variant first detected in the U.K.

“If you allow it to continue to spread, it will continue to evolve,” warns Lessells, who was part of the team that first identified the new variant in South Africa. The threat of mutation is greater if the virus is moving unhindered through large swaths of a country’s or region’s population. Lessells emphasizes that Africa is not the “problem” and that new variants could just as easily emerge elsewhere. Rather the issue is vaccine equity. “It is clear that if we leave Africa behind on the vaccine front, then there’s clearly a risk that it gets more challenging to control transmission,” he says.

The underestimation of COVID cases feeds into a narrative that African countries do not need vaccines as urgently as other nations. After all, if there are relatively few cases and deaths, then some people may say, “Good, no problem––they don’t need vaccines,” says Maysoon Dahab, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Her research estimated that only about 2 percent of COVID deaths in Khartoum, Sudan, were correctly attributed to the illness between last April and September.

Many African countries have initiated limited vaccination programs, mainly procured through the COVID-19 Vaccine Global Access (COVAX) Facility. Vaccines are earmarked for health care workers and extremely vulnerable groups. They are simply not available to inoculate entire African nations in the short to medium term—both as a result of global demand and because of rich countries hoarding doses.

Currently, rich nations accounting for 16 percent of the world’s population have bought 60 percent of the global vaccine supply, wrote World Health Organization director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in Foreign Policy last month. “Many of these countries aim to vaccinate 70 percent of their adult population by midyear in pursuit of herd immunity,” he wrote.

Vaccine-induced herd immunity is not likely for African countries in the near future. A spokesperson for COVAX co-leader GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, told Scientific American that the initiative aims to vaccinate 20 percent of people in its member countries by the end of the year. “COVAX’s work has only just begun: it is vitally important that manufacturers continue to support COVAX and governments refrain from more bilateral deals that take further supply out of the market,” the spokesperson said.

But if reported COVID cases are low, officials may struggle to persuade people to get a shot even if they are in a position to do so. The low reported disease numbers are bolstering vaccine hesitancy, warns Catherine Kyobutungi, executive director of the African Population and Health Research Center in Nairobi, Kenya. “People are asking why they need to be vaccinated when they’ve already gotten rid of the virus without vaccines,” she says.

Kenya has officially had 122,000 cases, but a nationwide blood-bank survey found that about 5 percent of more than 3,000 samples taken between last April and June contained SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. If extrapolated, this finding points to the possibility of millions of undiagnosed cases in Kenya, although some scientists say that the survey was not representative of the general population and could have had skewed results. Nevertheless, the country aims to vaccinate 30 percent of its population—a figure Kyobutungi describes as a “drop in the ocean”—by 2023.

Without widespread access to vaccines, African countries are relying on basic public health measures such as mask wearing and handwashing alone to control the disease’s spread. And, as with vaccination, people could dismiss these measures as unnecessary if the numbers misrepresent the risk of infection.

Governments may also take the statistics at face value and downscale their COVID surveillance efforts, Kyobutungi warns. That is, they may do so “until something terrible happens or, a year down the line, there’s a Malawian variant, a Ugandan variant or Sudanese variant,” she says. “If new lethal variants emerge in Africa, Africa gets cut off from the rest of the world, or the variants spread like the first cases in China. Then you have cases everywhere, and we need to vaccinate the whole world all over again.”

Others, however, are less concerned about undercounting and its potential consequences. Epidemiologist Salim Abdool Karim, co-leader of South Africa’s ministerial advisory committee, says that the only way to completely protect the public is to presume “everybody is potentially infected” and institute universal health measures such as mask wearing. “Vaccines are an important part of our prevention tool box—probably the most important part,” Abdool Karim says. “But they aren’t enough on their own.”

Ngoy Nsenga, WHO Africa’s program manager for emergency response, agrees that variants are a concern and that the best response is implementing public health interventions. “Of course, we wish we could have vaccines to vaccinate everyone and stop the chain of transmission, but because of availability, that is not possible,” he says.

Without worldwide concurrent vaccination, COVID will continue to spread. With the disease, African countries are “here for the long haul,” Nsenga says. And if that is true for the continent, it could well be true for the rest of the world. “If any place, any country, is not safe in this world, no country will be safe,” he says.

*Courtesy of Scientific American.

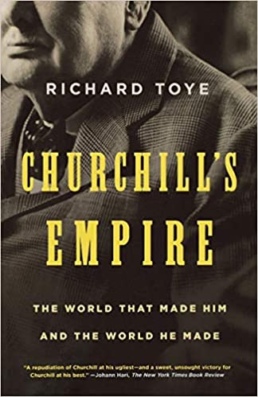

'Savages armed with ideas: more difficult to deal with' - Churchill's Empire

BOOK Except BY THE AUTHOR OF 'CHURCHILL's EMPIRE'.

Richard Toye.

Prologue.

On 10 December 1954 a visitor from East Africa was waiting on a horsehair sofa in the hallway of 10 Downing Street. Suddenly, the small, frail figure of Winston Churchill appeared from behind a screen, said, 'Good afternoon, Mr Blundell,' and offered him a slightly stiffened hand to shake. The two men went together into the Cabinet Room. It was only three o'clock but Churchill — smoking his customary cigar — ordered them both a strong whisky and soda. As they sipped their drinks, their meeting, scheduled to take fifteen minutes, spilled out to last forty-five. The topic was the Mau Mau rebellion against British colonial rule in Kenya; and Michael Blundell, a prominent white settler with a somewhat spurious reputation as a liberal, was given an impassioned exposition of the Prime Minister's views.

Churchill began by recalling his own visit to the country in 1907. Then, he had found the Kikuyu group, from which most of the rebels were now drawn, to be 'a happy, naked and charming people'. He professed himself 'astonished at the change which had come over their minds'. He became animated over the problem of how settlers might be protected from attack, and he poured out a flood of ideas designed to defend farmers: trip-wires, bells and other early warning systems. But in his view the issue was not really a military one — the problem was to get to the rebels' minds. His eyes grew tearful as he told Blundell of the threat the situation posed to Britain's good name in the world. It was terrible that the country that was the home of culture, magnanimity and democracy should be using force to suppress Mau Mau. 'It's the power of a modern nation being used to kill savages. It's pretty terrible,' he declared. 'Savages, savages? Not savages. They're savages armed with ideas — much more difficult to deal with.'

Over and again he pressed on a reluctant Blundell the need for negotiation, arguing that the strength of the hold the Mau Mau had on the Kikuyu proved that the latter were not primitive, stupid and cowardly, as was often imagined. Rather, 'they were persons of considerable fibre and ability and steel, who could be brought to our side by just and wise treatment'. He offered an analogy with his own role in finding a solution for the problem of Ireland after World War I, when he had negotiated with the nationalist leader Michael Collins, once a hard-line terrorist opponent of the British. Churchill also deplored British brutality against the Kenyan rebels and the fact that so many of the local population were locked up in detention camps, before offering his views on race relations. He was old-fashioned, he said, and 'did not really think that black people were as capable or as efficient as white people'. All the same, 'If I meet a black man and he's a civilized educated fellow I have no feelings about him at all.' He showed some scepticism about the white settlers too, 'a highly individualistic and difficult people', although he put some of their attitude down to 'tension from the altitude' in the highland areas in which they lived.

When Blundell asked him for a message of encouragement to pass on to them, he declined, but, as his visitor got up to leave, Churchill assured him that he was on the right path and had his support. Blundell wished him a slightly belated happy eightieth birthday, and the Prime Minister looked greatly touched. He was beginning to feel his age, he said. Then he revealed a secret that had been kept from the outside world: 'Hm. I've had two strokes. Most people don't know that, but it's a fact. I keep going.' Blundell deduced that this accounted for the stiffened handshake at the beginning. Churchill walked him to the exit of the room and then, when Blundell had gone about five steps into the hall, wished him goodbye and good luck.

This conversation did not mark any great turning point in the history of Kenya. Churchill, just months from retirement, was no longer in a position to be a major influence on colonial policy. Nevertheless, it was highly revealing of his attitudes to race and Empire, touching numerous themes that had been present throughout his career. There were so many familiar hallmarks: the gift for a phrase ('savages armed with ideas'), the recollection of a happier, more innocent past, the emphasis on magnanimity and negotiating from strength. Also familiar was his unashamed belief in white superiority, a conviction which, for him, however, did not lessen the need to act humanely towards supposedly inferior races that might, in their own way, be worthy of admiration.

Recognizable as part of this was his opinion that members of these races might earn equal treatment, if not exactly warm acceptance, provided they reached an approved cultural standard: a 'civilized educated' black man would provoke 'no feelings' in him. Overall, the striking thing is the complexity of his opinions. He emerges from Blundell's account of the discussion as a holder of racist views but not as an imperial diehard. He comes across in his plea for peace talks as a thoughtful visionary, but also, in his description of the formerly 'happy, naked' Kikuyu, as curiously nïave about the realities of imperialism. He was prepared to question the conduct of a dirty colonial war, but was in the end willing to assure its supporters of his backing.

Churchill's conversation with Blundell is a good starting point for consideration of his lifelong involvement with the British Empire, and the general attitudes to it from which his specific policies flowed. In order to do this we need to contend with his reputation — or reputations — on imperial issues. The popular image of him, which draws in particular on his opposition to Indian independence in the 1930s and 1940s, is of a last-ditcher for whom the integrity of the Empire was paramount. Yet many of his contemporaries had viewed him differently. As a youthful minister at the Colonial Office in the Edwardian period, political antagonists had described him as a Little Englander and a danger to the Empire. ('Little Englandism', which today carries connotations of anti-European xenophobia, at the time implied opposition to imperial expansion and to foreign entanglements in general; it was often used as a term of abuse.) As late as 1920, even the wild-eyed socialist MP James Maxton would claim disapprovingly that 'the British Empire was approaching complete disintegration' and that 'it was not going too far to say that Mr Churchill had played a primary party in bringing about that state of affairs'. Such critics, it should be noted, were not alleging that Churchill was actively hostile to the Empire, more that it was not safe in his hands or that he was comparatively indifferent to it. By the time of Churchill's final term in office, this view was still maintained by a tenacious few.

In 1953 the Conservative politician Earl Winterton wrote to Leo Amery, one of Churchill's former wartime colleagues, to congratulate him on the first volume of his memoirs. He told him: 'I am particularly pleased that you have, whilst paying a tribute to Winston's great patriotism, stated, which is indubitably the case, that he has never been an imperialist in the sense that you and I are; we suffered from this point of view during the war, whilst we were in opposition after the war and are still suffering from it to-day.'

Although similar opinions can be found in the historical literature, such contemporary opinions of Churchill need to be treated with some caution. Those who accused him of not caring enough about the Empire often meant, underneath, that he did not happen to share their particular view of it. Nor is the conventional image completely misleading. Although during his post-1931 wilderness years Churchill publicly disclaimed the diehard label, it is clear that he came to revel in it. During the war, the topic of India frequently triggered such extreme reactions in him that he sometimes appeared not quite sane. Nevertheless, this man who could be so disdainful of non-white peoples — 'I hate people with slit eyes & pig-tails' — also had another side to him. In 1906, when criticizing the 'chronic bloodshed' caused by British punitive raids in West Africa, it was he who sarcastically wrote: 'the whole enterprise is liable to be misrepresented by persons unacquainted with Imperial terminology as the murdering of natives and stealing of their lands'. As his talk with Blundell shows, this concern for the welfare of subject peoples stayed with him until the end of his career.

In 1921, as Secretary of State for the Colonies, he stated that within the British Empire 'there should be no barrier of race, colour or creed which should prevent any man from reaching any station if he is fitted for it'. Yet he immediately qualified this by adding that 'such a principle has to be very carefully and gradually applied because intense local feelings are excited', which was in effect a way of saying that its implementation should be delayed indefinitely. As one Indian politician put it the following year, when noting Churchill's seemingly inconsistent position on the controversial question of Asians in East Africa, it was 'a case, and a very strange case indeed'.

Excepts from the book Churchill's Empire by Richard Toye.

The state of instructional technology in pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial Africa: A survey of literature

Godwin Haruna.

Abstract.

This article examines the evolution of instructional technology in pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial Africa’s educational system through a survey of existing literature. It stresses the position that education pre-dates colonization of Africa as customary education taught morals and the essence of communal living from the cradle with the goal of molding decent human beings who would preserve the cultural heritage of the people. However, with colonialism, beginning with the Portuguese, who first introduced their brand of education in the continent, the earlier focus was fundamentally altered to making the African embrace the mannerisms and ways of life of the colonists. This trend continued with the British, French, and German colonial administrators who balkanized Africans among themselves. As the literature on the subject revealed, what started as distance learning through the aid of radio and television metamorphosed into many variants. The paper noted that the emergence of the computer and the accompanying internet connectivity has made instructional technology the talking point in many educational settings across the continent.

Keywords: Instructional technology, educational technology, information communication technology, distance learning, e-learning.

Introduction

There have been many definitions of technology as a concept by as many scholars that broached the topic over time. One that is particularly significantly related to the subject matter was by Saettler (1968):

The word technology does not necessarily imply the use of machines, as many seem to think, but refers to any practical art using scientific knowledge (p. 2) as cited in Gentry (2011).

A further clarification of the ‘practical art’ suggested technique, which makes possible the instructional applications of the machine. Technology has undoubtedly revolutionized learning, in the same way it has transformed all aspects of human endeavor in modern times. Kohut, Taylor, Keeter, Parker, Morin, and Cohn (2010) argue that significantly, technological change and generational change happen to be two sides of the same coin as they move together side by side in a natural progression.

Another perspective on the definition was by Simon (1983):

Technology is a rational discipline designed to assure the mastery of man over physical nature, through the application of scientifically determined laws (p. 2) as cited in Gentry (2011).

There is a connection between this definition that presupposes the mastery of man over nature with attempts to leverage technological development in information technology to improve learning outcomes in educational institutions. Related to the topic also, is the perspective of Finn (1960):

In addition to machinery, technology includes processes, systems, management and control mechanisms both human and non-human, and… a way of looking at the problems as to their interest and difficulty, the feasibility of technical solutions, and the economic values – broadly considered – of those solutions (p. 2) as cited in Gentry (2011).

Instructional technology, broadly speaking, is leveraging Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) to impart knowledge in educational institutions. Education per se, brought instructional technology to Africa.

Education as an avenue to learn new things preceded the colonialists who held sway over African countries for several decades in their colonizing mission. In various parts of Africa, customary education taught morals and the essence of communal living from the cradle. In the traditional African society (pre-colonial), education was stepped down through the family, clan or village settings (Mazonde, 1995). It was organized in such a way that everyone, especially among the adults, had a role to play in the proper upbringing of the younger members of the society. The importance of being your brother’s keeper was the underlining factor in the morals taught to the younger elements in face-to-face settings in the absence of technology. Basically, the methods of stepping down instructions were both formal and informal.

Mazonde (1995) situated much more poignantly, the main objectives of the African customary education; firstly:

To preserve the cultural heritage of the extended family, the clan and the tribe. Secondly, to adapt members of the new generation to their physical environment and teach them how to control and use it; and to explain to them that their own future, and that of their community, depends on the understanding and perpetuation of the institutions, laws, language and values inherited from the past (p. 2).

In contrast, the purpose of colonial education, in addition to helping the colonists in the colonial civil service, was to make the African become a complete European in thoughts and in deeds. This position was succinctly put by Wa Thiong’o (1981), a Kenyan scholar, who noted that:

the process annihilates a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves. It makes them see their past as one wasteland of non-achievement and it makes them want to distance themselves from that wasteland. It makes them want to identify with that which is furthest removed from themselves (p. 3).

The advent of colonialism by the European political elite and the collaborating missionaries and their business counterparts brought to Africa what is today known as modern education. This genre of European-style education, which was first started by the Portuguese missionaries in the fifteenth century, was popularized by other European missionaries across Africa in the eighteenth century in the wake of colonialism (Mazonde, 1995). The British, French and Portuguese colonial administrators formed a perfect partnership with the missionaries in the spread of this Western-style educational system in the various African countries where they had a foothold.

Then, school was the special prerogative of the children of kings, colonial civil servants and the nouveau riche of the society. With the imperial powers’ wholesale involvement in the educational nurturing of Africans began the gradual introduction of technology into the school system as it evolved in the various metropolitan countries over time. However, at the initial stages, Mazonde (1995) noted that the educational emphasis was on liberal arts as there was not much of instruction in the technical, vocational and professional fields. Instructions were stepped down directly through a class-style sitting of face-to-face arrangements as instructional technological aids were a rarity.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to review the state of access, utilization and quality of instructional technology during the pre-colonial, colonial post-colonial periods in Africa. With the way the rest of the world is adapting to changes in information and communication technologies in pedagogy, Africa’s growth in ICTs appears to be sluggish. This article highlights some of these inadequacies with a view to putting them before educational policy makers on the continent. Advancement in educational offerings in this new information age is viewed through the lenses of the progress attained in forging ICTs strategies in instructional technology.

Research Questions

Based on the gradual evolution of instructional technology approaches into the African educational system, the research questions that guided this study are: What has been the state of instructional technology in Africa during the pre-colonial and colonial periods? What is the level of access, utilization and quality of instructional technology in post-colonial Africa? A survey of literature in selected African countries would unearth the clues.

Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

Instructional technology applications in educational settings evolved to aid learners realize learning outcomes through the channels of multi-media, CD ROM, projectors, as well as the Internet. In precolonial and colonial periods in Africa, these modern innovations that aided instructional technology in the classroom were rare in the same way that literature on them are not readily available. In contrast however, the post-colonial era became the boom time for instructional technology solutions in the classroom and many African countries have embraced the synergies amid some hiccups . Due to its phenomenal impact on students’ learning, many of the countries on the continent have enacted IT policies to guide implementers of this strategy that has thrown up many vistas of learning. As literature would show on access, utilization and quality of instructional technology in mainly post-colonial Africa, amid the glitches being experienced by many countries in the region, there is no let off in creating a favorable environment for this strategy to thrive.

Access to instructional technology

There is dearth of literature on any form of instructional technology as contemplated in the definitions by Saettler and Simons in Gentry (2011) during the pre-colonial and colonial epochs in Africa. However, technological approaches to instruction were being gradually deployed in the immediate post-colonial period owing to the massive enrollment witnessed across all schools in the provision of education in the various African countries. These forms of technological strategy of instruction in African education began in the wake of the measured introduction of distance learning through television and radio broadcasts as means of educating the mass of the population (Mazonde, 1995). In many African countries open universities have emerged as a potent way learning through technological aids in the modern era. Technology has, understandably, remained a boon to education and it has changed the face of learning in various societies across the world including Africa. Clearly, the evolution of multi-media channels, CD ROM, projectors and the like in classroom instruction have advanced the cause of learning in later epochs in Africa (Okah, 2010).

How does technology aid educational pursuit? Simply put, technological synergy in the educational arena is euphemism for e-learning or online learning as well as the use of other electronic aids to step down learning. Okah (2009) defined e-learning as the online delivery of information. In another paper, Okah (2010) saw the concept as integrating learning with technology. This definition subsumes the use of all electronic aids for learning purposes. For Landon and Landon (2010), e-learning is synonymous with instruction distributed through purely digital technologies such as CD ROM, the internet and private networks. In their own perspective, Hagg, Cumming, and Dawkins (2000) saw the concept of tele-education in various dimensions, among them, e-education, distant learning, distributed learning, and online learning, which are all delivered through various channels of Information Technology (IT) such as chatrooms, video-conferencing, e-mails and the internet. It is a form of self-directed learning that has assumed an important place in education, which affords students greater autonomy and leaner control.

Technology has undoubtedly revolutionized learning, in the same way it has transformed all aspects of human endeavor in modern times, and Africa has not been left behind in the scheme of things especially in the post-colonial era. Significantly, technological change and generational change happen to be two sides of the same coin as they move together side by side in a natural progression (Kohut, Taylor, Keeter, Parker, Morin, & Cohn, 2010). One of the strategies that facilitates active learning in educational institutions in this age is text messaging, due essentially to its instantaneous effect. Innovative mobile learning has assumed a very significant portion of educational offerings in Africa, and applications such as Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS), Short Message Service (SMS), which is also euphemism for text messaging, internet-based tools, mobile phones and the others have become avenues to promote learning (Gurocak, 2016). The mobile phone’s portability, coupled with its wide reach to populations far and near, has increased its attractiveness in educational settings and faculty across African schools have taken advantage of its offerings.

Over the years, the emergence of mobile wireless technologies has been a source of enthusiasm among professionals in industry and, especially, faculty in higher educational institutions because of its potential in shifting the classroom learning environment from the conventional settings to mobile learning (Kims, Mims, & Holmes, 2006). The advantage of wireless technology over the erstwhile wired technology is huge given its limitless freedom to operate from anywhere regardless of time and location and this is where text messaging through mobile phones remains one of the attractions in the mobile learning technologies of this era.

Kims et al made a clear distinction between mobile or wireless technologies and mobile wireless technologies. Specifically, Kims et al defined mobile wireless technologies as:

Any wireless technology that uses radio frequency spectrum in any band to facilitate transmission of text data, voice, video, or multimedia services to mobile devices with freedom of time and location limitation (p. 79).

This is where the mobile phone electronic device perfectly fits into the freedom of being located anywhere, anytime into the context of using it for instructional purposes for students. Many Educational institutions in Nigeria, for instance, have adopted this technological approach towards instructions in various schools across the nation.

Elsewhere in the Southern African nation of Zimbabwe, the country is still grappling with acquiring basic utilities such as telecommunication infrastructure, hardware, software and networks and it is only when these are easily available that consideration could be extended to serious educational and training issues like pre-service teacher education and integration of technology instruction (Chitiyo & Harmon, 2009). The paper noted that there was the urgent need for African countries to develop the use of ICTs in instruction in order to revitalize African universities to meet the crucial needs of the population in the 21st century. Chitiyo and Harmon noted that the political instability in Zimbabwe in the last ten years has not only seriously incumbered the growth of technology instruction but has culminated in the backward slide of ICTs capabilities in the country. It was the contention of the paper that the situation in Zimbabwe was a true reflection of what has been happening in other African countries as it relates to technology integration into educational instruction.

In the East African country of Tanzania, there are a legion of factors militating efforts towards institutionalizing instructional technology in order to liberalize access to the majority of people. According to Hennessy, Onguko, Namalefe, and Naseem (2010), some of these constraints include inadequacy of electricity supply which culminates in incessant power outages, poor technology infrastructure, large classes and overcrowded computer labs, low bandwidth, high costs of (mainly satellite) internet connectivity especially for rural schools located outside the national telecommunications network and electricity grid, software licenses and equipment maintenance, insufficient and inappropriate software. Added to these hiccups, the authors stated that there was also lack of qualified teachers to birth a seamless integration of instructional technology. They called for a proactive government policy that would drive ICTs integration policies in the country’s educational system.

Utilization of instructional technology

The West African country of Nigeria, which has a blossoming Internet connectivity reach in both rural and urban locations has a national information and communication technologies’ (ICTs) policy that is geared towards the education of the mass of the people. Since one of the fundamental features of the Nigerian IT policy is to leverage the huge potentials of ICTs to enhance education, it also has one of its general objectives of fostering pedagogical innovation in the area of e-learning (Vooslo, 2012). The Nigerian IT policy was approved more than two decades ago, and it became fully operational almost immediately. As at today, virtually all universities (both public and private) and other allied institutions have Internet connectivity that navigate their operations using the processes of the new information age. Other levels of educational training are leveraging the potential of instructional technology in advancing the cause of learning.

In higher educational institutions across Nigeria, a study by Allen and Seaman (2013) stated that as at 2012, more than 6.7 million students participated in at least, an online course in pursuit of their various educational degrees. This represents the growing number of students signing up to the technological platform of learning which is fast taking roots in the country. The frequent labor disputes over wages and provision of other amenities between the members of the academic community and the Nigerian government, which owns most of the universities, have increased the attractiveness of online learning. When such disputes result in closure of classes, people resort to online course offerings to satisfy their educational diet.

In another West African country of Ghana, where the ICTs revolution has since taken roots in the educational institutions, a study conducted by Boabeng-Andoh (2012) noted that there is a positive correlation between the use of ICTs and the teachers’ competence. The study noted further that both traditional and adult learners appreciate the integration of ICTs into their study. Computer technologies remain the most essential information and communication technology tools being deployed in the world today, and with increased pressure on educational institutions in Nigeria to do more with less resources, ICTs has come to the fore as the veritable instrument to realize the goals of education for many more people (Nwachukwu, Eke, Uzorka, Ekpenyong, & Nte, 2009).

In a policy brief on the instructional technology situation in South Africa, Mdlongwa (2012) contended that the resort to ICT in educational institutions to improve learning could assist in overcoming some of the difficulties of improving the effectiveness and productivity of both learning and teaching in the country’s schools, and in the process, reduce the digital divide. The paper noted that ICTs utilization in South Africa was not at the desired point since out of a population of 48 million as at 2002, only about three million had internet access. However, since the introduction of computers to South African schools beginning with private, and then public, in the 1980s, the growth of its widespread use has been very sluggish owing to paucity of funds and lack of prioritization among competing demands.

Quality of instructional technology used

In their appraisal of this strategy, Iloanusi and Osuagwu (2009) contended that ICTs-enhanced instruction tended to stimulate critical reasoning and provided a much wider variety of means for accomplishing educational goals. Nwachukwu, et al (2009) also stressed that while there might not be any iota of illusion that instructional technology would address all the challenges of education, but there is no denying the fact that technology has intruded into every facet of life in today’s world. The use of internet-enabled strategies to step down instruction, has, therefore, become widespread among educational institutions in most African countries, ostensibly, for ease of learning in the post-colonial era. It is the contention of Nwachukwu et al (2009) that ICT boosts value to the methods of learning and to the organization and management of learning institutions. The paper noted that technologies are a driving force behind much of the development and innovation in both developed and developing countries, and this would explain why African countries keyed into the strategies in the post-independence era.

In Nigeria, Yusuf (2005) stressed that ICT has contributed to the quality and quantity of teaching, learning, and research in conventional and distance educational institutions in the country. This it does by its dynamic, interactive, and appealing content; and it also provides real prospects for individualized instruction. However, despite these overwhelming advantages, the quality and spread of ICTs is at a low ebb in Africa. Yusuf contended that with a total contribution to world population standing at 12 per cent, the continent has just about two per cent presence in ICTs use in its operations. The reasons accounting for this appalling situation could be attributed to low Internet connectivity, inadequate access to ICTs infrastructure and low involvement to software development. This overall poor quality has undoubtedly affected the rapid integration of instructional technology strategies in all facets of educational offerings. Against this background, the Nigerian ICTs policy has as one of its major themes the integration of IT into the mainstream of education and training.

In the East African country of Kenya, there are complaints against the quality of instructional learning facilities. Ndirangu and Udoto (2011) noted that the quality of the library, online resources and lecture facilities provided by Kenyan public universities have failed to meet the test of quality. The paper added that institutions were incapable of supporting the desired educational programs effectually in order to facilitate the development of learning environments that support students and teachers in realizing their objectives. In a policy brief on the situation in South Africa, Mdlongwa had made similar complaints about disjointed facilities which has affected the smooth utilization of ICTs solutions on a wider scale.

Methodology

Fundamentally, this article sprang from a survey of literature on the subject of instructional technology in pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial epochs in Africa and the need for its uptake in current educational offerings across the continent. Relying on a variety of literature on the subject, the intent is to examine the state of access, utilization and quality of instructional technology during the pre-colonial, colonial post-colonial periods in Africa. The article explored the extent of instructional technology integration into the educational systems in selected African countries under the various epochs. The countries include Nigeria, Kenya, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Ghana and Tanzania, among others. As would be expected, the development of technology infrastructure and the accompanying components were the major challenges for the countries at the very early stages of their nation-building. This proved a major concern for many others that hindered appreciable progress.

Databases such as Google Scholar, ERIC, and JSTOR were the sources of data from where all the relevant articles came for scrutiny. The procedure was to use keywords such as instructional technology, educational technology, information communication technology, distance learning, e-learning in Africa using the resources of the Ohio University Alden Library to generate the articles. Once the articles were assembled from the aforementioned data bases, we used the keywords of access, utilization and quality of instructional technology as the rubrics of analysis of integration in the selected African countries during the various epochs from the selected articles. The table below shows related articles on the various search engines from where the reviewed articles emanated.

| Database | Keyword | Documents |

| Google Scholar | Inst. technology in Africa

Information comm, technology e-learning in Africa Distance learning in Africa |

159, 000

3, 400 71, 000 2, 590, 000 |

| ERIC | Inst. technology in Africa

Information comm, technology e-learning in Africa Distance learning in Africa |

33, 335

245 106 18, 702 |

| JSTOR | Inst. technology in Africa

Information comm, technology e-learning in Africa Distance learning in Africa |

6, 144

54, 457 1, 050 45, 592 |

Findings, Discussion, and Analysis

To effectively deal with the research questions for this paper, this section has been broken into the precolonial and colonial epochs. Thereafter, the findings and analysis would turn its searchlight on the post-colonial period when this revolutionary instructional technology synergies were birthed in Africa. Under the postcolonial period, we examine closely the topical issues of access, utilization and quality of instructional technology strategies that are on offer in the selected African countries.

Precolonial and colonial epochs

From the definitions of technology offered by Saettler and Simon as cited in Gentry (2011) earlier in this paper, it is worth noting that the customary education offered in pre-colonial African societies was devoid of any scientific body of laws. Although it is within the realm of knowledge passed on from one generation to the other, there was no extant body of scientific laws guiding it. To that extent and related to Mazonde’s (1995) description of the type of education offered in that era, instructional technology synergies as we know them today, were practically non-existent and therefore, inapplicable. Colonization by European imperialists supplanted the pre-colonial era as European missionaries and their business collaborators established their foothold across Africa.

As Ngugi wa Thiong’o (1981) contended in his treatise, colonial education came with the idea of Europeanization of Africans to fit into the colonial civil service. Also, Mazonde (1995) noted that the educational emphasis was on liberal arts as there was not much of instruction in the technical, vocational and professional fields. Suffices to say that instructions were stepped down directly through a class-style sitting of face-to-face arrangements as there was little semblance of instructional technological aids. So, for most of Africa, instructional technology was not a feature of their educational offerings during the colonial period with the exception of a few who remained under colonization until the 1980s. Related to the first research question therefore, it can be argued that there was little or nothing of instructional technology in the educational systems of both pre-colonial and colonial periods in Africa. Since we cannot establish the use of instructional technology applications in both precolonial and colonial eras, it would be difficult to contemplate its access, utilization, as well as quality.

According to Mazonde (1995), in the pre-colonial era, customary education was mostly stepped down through one-on-one family circle or via the instrument of peer groups as passed on from one generation to the other. The family setting was the strongest citadel of learning, and any aberrant behavior was dealt with at that level before it rears its ugly head in the public sphere. Effectively, what we know as instructional technological aids in the modern era were absolutely non-existent. The colonial setting was a little different even though it was also devoid of any tangible technological aids. This is because, in the Western metropolitan countries, which were lording it over the colonies at the time, what is today known as instructional technology education were equally absent. Therefore, you cannot give what you do not have or you give little of what you have! However, to meet the requirements of the colonial civil service as stressed by Ngugi wa Thiong’o (1981) colonial education was organized in class-style setting of students being grouped together with the teacher at the helm leading the instruction for them. It was an improvement over the pre-colonial variant as students progressed to the next level of education based on their mastering of content taught in their class.

Post-colonial period

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), computer technologies and other aspects of digital culture have changed the ways people live, work, play, and learn, impacting the construction and distribution of knowledge and power around the world (1984). The United Nations agency believes that science and technology are crucial components of development and growth, and many of the problems of underdevelopment had been attributed to weak indigenous science and technology capacities, inappropriate technological choices, poor technological development policies and dependency-producing transfers of technology (UNESCO, 1984). To redress this, since 1968, UNESCO aggressively advocated for developing countries (a large chunk of which are in Africa) to pursue science and technology policies that would aid sustainable development (UNESCO, 1984). Since most of the countries in Africa had become self-governing by this time, it was the spur of the moment that crystallized into the various technology-enhanced educational policies by the various countries on the continent in order to put technology at the center of development.

Another United Nations agency at the forefront of campaign for learning globally is the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and its work has been very remarkable in the post-colonial period in Africa. Based on its entrenched policy of “Every child has the right to learn”, UNICEF advocates strongly for the right to education for the world’s children . Even though UNICEF (2019) statistics show that over one billion children go to class daily around the globe, yet another 617 million children and adolescents around the world are unable to reach minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics – even as two thirds of them are in school. In fact, the statistics estimate that one in five children are entirely out of school globally. Unfortunately, a sizeable number of these are in crisis-torn African countries and others ravaged by poverty, the main factors fueling the unfortunate development. Over the years, in addition to working in health-related fields on the continent, UNICEF tacitly promotes education under three planks. These include, access, where it advocates gender equity, learning and skills, under which it advocates quality learning outcomes and skills development where innovative instructional technology aids are taught, and finally, emergency and fragile contexts, where it campaigns for improved learning and protection during emergencies.

As postulated by Kohut et al (2010), technological change is synonymous with generational change as humanity undergoes transformation over time. Therefore, the post-colonial period started in the age of fast-paced technological innovations, which was complemented by the emergence of internet connectivity. These advances in technology and information dissemination synergies across the globe hastened the introduction of instructional technology solutions in Africa’s educational offerings. This development upped the ante for African countries, which prompted some to begin the enactment of IT policies as studies such as Vooslo (2012), Yusuf (2005), and Okah (2010) showed on Nigeria, Mdlongwa (2012) on South Africa, as well as Chitiyo and Harmon (2009) on Zimbabwe. As these developments unfolded all over Africa in the years following independence, we will briefly look at access, utilization, and the quality of the offerings in the selected countries. With the gradual implementation of these policies in the various countries, instructional technology aids were being launched at all levels of educational offerings.

Access to instructional technology

In terms of access, as the post-colonial advances in the use of instructional technology in educational institutions continue to expand, Nigeria has recorded a surge in recent years. Studies by Allen and Seaman (2013) showed that as at 2012, more than 6.7 million students participated in at least, an online course in pursuit of their various educational degrees. Also, in Ghana, a study by Boabeng-Andoh (2012) noted that there was a positive correlation between the use of ICTs and the teachers’ competence as the bug of instructional technology spreads in educational institutions in the country. Also, as reported by Mdlongwa’s (2012) policy brief on South Africa, there is also a growing awareness and utilization on the use of ICTs solutions in educational offerings.

In the East African country of Kenya, the government’s revolutionary development blueprint christened “Vision 2030” formulated the policy of one laptop per child in order to avail the children the opportunity of using computer for learning to quicken their migration into the digital age (Waga, Makori & Rabah 2014). Besides entrenching the digital culture from the elementary school as proposed by the Vision 2030 laptop agenda, the study focused on the efforts to build a centralized digital content repository containing e-learning resources, research applications and tools with a collaborative on-line modern digital library accessible with a controlled right based accessibility in the country. The Kenyan approach to digitization was engineered to assist students on the e-learning synergies which would address the dwindling instructor-student ratios while universities and research institutes through collaborative ventures would participate alongside their international colleagues with immediate innovation promoting the local industries. Although, the implementation of the one laptop per child policy in Kenya has attracted criticism over cost and other issues, it remains a right step at the right time that would bridge the rural-urban divide given that the world has moved on towards knowledge economy.

Utilization of instructional technology

Henessy et al (2010), and Chitiyo and Harmon (2009) had noted on Tanzania and Zimbabwe respectively, that utilization of instructional technology applications is confronted with a lot of challenges. Tanzania is confronted with issues that include inadequacy of electricity supply which culminates in frequent power outages, poor technology infrastructure, large classes and overcrowded computer labs, low bandwidth, and high costs of (mainly satellite) internet connectivity. On its part, Zimbabwe is contending with acquiring basic utilities such as telecommunication infrastructure, hardware, software and networks in order to bolster instructional technology applications in its educational system. Despite all these hiccups, however, instructional technology synergies are reportedly in use in the countries’ educational systems. In Nigeria where appreciable progress appears to have been made integrating instructional technological aids into class offerings, the issue of frequent power outages remains a major obstacle to educators. Even where equipment are available, lack of power to operate them has constituted a major barrier towards seamless class use.

Quality of instructional technology used

While it is indisputable that there is appreciable level of access and utilization across African countries in the use of instructional technology solutions in educational institutions, the quality of what is on offer appear problematic in most of these countries. Studies by Okah (2010) on Nigeria, Chitiyo and Harmon (2009) on Zimbabwe, Ndirangu and Udoto (2011) on Kenya, as well as Hennessy et al (2010) on Tanzania aptly capture the problems being experienced in these countries, which are summed up in problematic technology infrastructure and strong foundational policy initiative. Okah (2010) noted that the problem of paucity of funds to execute technology-related educational programs was at the core of the challenges facing the quality of what is on offer. Undoubtedly, Africa has come a long way to arrive at its present epoch of access and utilization, yet there is a long way ahead to reach the desired level of quality. This is a challenge that must be overcome.

Given the fact that access and utilization are both driven by the quality of Internet connectivity in operation in the various countries, it is worthwhile to scrutinize the demographics of the people who have Internet connectivity in the various countries in the table shown below. As at 2012, figures obtained from the Internet World Statistics showed that Nigeria, which had the highest population of Internet users on the continent, was ranked 129th on the world’s fastest broadband speed. This would clearly impact negatively on utilization of technology modulated instruction in the various levels of educational offerings across the country. All the other African countries surveyed ranked poorly on the broadband speed, and this reflects the conclusions of Henessy et al (2010), and Chitiyo and Harmon (2009) on Tanzania and Zimbabwe, respectively, all of which cited poor foundational infrastructure as the bane. The studies show a similarity of conclusions on poor infrastructure impacting negatively on access, quality and utilization.

Recommendations

Recommendation for policy makers: In the new world information order that has birthed the globe’s knowledge economy, Africa’s educational offerings must embrace all the dynamics of instructional technology synergies to remain competitive and take active part. Anything otherwise is suicidal and counterproductive. Studies by Okah (2010), as well as Chitiyo and Harmon (2009) have acknowledged that the digital divide between Africa and the rest of the world is huge. Therefore, the only option left for education policy makers in Africa is to rise to the occasion and ensure that the current wide gap is substantially reduced. The pathway to this reduction, is the enactment of favorable and strong policies consciously designed to institutionalize instructional technology strategies in all levels of educational offerings on the continent. Therefore, it is high time African leaders seized the initiative and rebuild the existing fragile infrastructure through proactive policies.

Recommendation for practitioners: The reality of today’s world is that the much-touted technology transfer is a mirage and practitioners must rally and deepen integration of technology in educational offerings. To that extent, African governments must prioritize human resource development by investing in capacity building and training of the personnel in the education sector in order to realize the objectives of raising a new army of competitive graduates that could hold their own among contemporaries from across the world. Enough financial resources should be devoted to building technology infrastructure across the landscape to enable organizations and educational institutions leverage upon them to firm up their instructional technology synergies. Instructional technology solutions should be made available and taught across all levels of educational institutions beginning with the kindergarten to the tertiary education offerings. The idea of catching them young should not be lost on policy makers in future, and one such laudable initiative to be embraced by other African countries is the one laptop per child policy in Kenya. Given the huge potential of technological synergies, it’s a win-win situation to play active role. Development scholars have linked technological advancement to overall development of a nation, therefore, it is sine qua non for the continent to embrace technology in order to make a headway.

Recommendation for future research: This article had been developed before the unprecedented COVID-19 health challenge, which practically paralyzed the entire world. Many countries of the world with the requisite technology infrastructure quickly reverted to remote working for their workforce and learning for their educational institutions across all levels. You could still feel motion even amid the lockdown that pervaded these countries, but many African countries apparently lagged behind, understandably! Future researchers should examine closely how African countries could synergize post-COVID-19 and tap from technological advances in their educational offerings. It is only a deepening of technology at all levels of educational pursuits that could galvanize efforts towards desirable development.

Conclusion

It is incontrovertible that the advent of technology has reshaped the modern world in so many ways never contemplated. From the definition of technology by Saettler and Simon as cited in Gentry (2011), it is obvious that instructional technology was absent from the category of customary educational offerings prevalent in African societies in the precolonial age. However, the colonial era came with some semblance of instructional technology, which was built upon in subsequent years of development. Although the colonists came with their policy of Europeanization of Africans according to Ngugi wa Thiong’o (1981), the gradual introduction of instructional technology in educational offerings began in that era. This was essentially to reflect the technological changes taking place in the metropolitan countries, since ipso facto, the territories were their extensions overseas, they also benefited from the changes.

Significantly, instructional technology blossomed in various African countries in the post-colonial era. The United Nations agencies led the way in advocating for educational technologies into African schools’ curriculum. Of particular importance is UNESCO’s conviction that computer technologies and other aspects of digital culture have changed the ways people live, work, play, and learn around the world, and Africa and other developing countries must factor into its offerings to meet the goals of development. This advocacy facilitated policy initiatives that expanded the space for instructional technology for schools in Nigeria (Okah, 2009), the Vision 2030 blueprint in Kenya (Waga, Makori and Rabah 2014) that facilitated the distribution of laptops to schoolchildren and several such actions by the other countries on the continent. UNICEF was also a contributory factor to the growing awareness of computerization and instructional technology in several African nations through its collaborative activities with the governments in the post-colonial era.

It is worthy to note that the expansions taking place in the various countries were not without hitches. Several studies, including Okah (2010) on Nigeria, Chitiyo and Harmon (2009) on Zimbabwe, Ndirangu and Udoto (2011) on Kenya, as well as Hennessy et al (2010) on Tanzania have highlighted problems associated with quality, access, and utilization in the various countries. A major hiccup common to all these countries is the issue of poor communication infrastructure, which would require a deft political will to resolve in order to put the continent on the proper path to integrating instructional technology in its educational offerings. The lackluster development of instructional technology on the continent is aptly surmised by the statistics from Internet World, which showed that Nigeria, which had the largest population of Internet users in Africa, was ranked 129th on the world’s fastest broadband speed. The best ranked African country, Ghana, was put at a distant 73rd! In modern times, fast Internet drives pedagogical instructions in the wake of online classes and other hybrid variants of educational pursuits. What this means in effect is that, although the countries have since introduced one form of instructional technology or the other, a lot still remains to be done.

References