Religion and Democratization

By Michael D. Driessen.

"This is among the most important recent books on religion and democracy. Michael Driessen insightfully and convincingly challenges the prevailing wisdom among many liberal thinkers, arguing that religion and state are not only compatible in democracies but that a religiously friendly democratization process is possible. He supports this contention with an in-depth analysis of contemporary and historical examples from Catholic and Muslim majority states as well as a wide-ranging statistical analysis which also shows when and why this process succeeds or fails." --Jonathan Fox, Professor in the Department of Political Studies, Bar Ilan University

"How can a religious community that is unfriendly toward democracy come to adapt itself to democracy? Few questions are more burning in global politics today, especially with respect to the role of Islamic countries. In his first book, young scholar Michael Driessen answers this question with creativity, careful research, and convincing force. He offers an answer that both secularists and religious people will have to take seriously if they favor democracy, stability, and peace. In doing so, he contributes a defining work to the still formative field of religion and global politics." --Daniel Philpott, Professor of Political Science and Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame

"By using historical cases that draw comparisons between political systems influenced by Catholicism and Islam, Religion and Democratization acts as a starting point for further debate about incorporating religious actors into the democratization process." --Middle East Journal

"[P]rovides an excellent combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis. This is an impressive and original work of comparative politics, based on detailed research in both political science and religious studies and fieldwork in Algeria. Highly recommended." -- CHOICE

Inequality: What Is To Be Done?

By Anthony Atkinson.

Reviewed by Tom Clark.

“You say you want a revolution,” sang John Lennon, before adding a characteristic barb: “we’d all love to see the plan”.

The way the world’s economic establishment discusses inequality invites a Lennonist response. After decades of denying any problem, it came to accept that there was an issue during the slump. Just before taking office, David Cameron would invoke The Spirit Level, and – more recently still – earnest executives have chatted about Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st century at Davos. It is terrific that such books have become fashionable, but as long as the discussion remains in the realm of generalities – as long as we haven’t seen “the plan” – it will be less than threatening to the have-a-lots, and less than useful to the have-nots.

In this new book, the doyen of inequality economics in the UK, Anthony Atkinson – whose many students have included Piketty – sets out what a real plan for reducing inequality would look like. Where Piketty illuminated his data with the sweeping categories of a continental intellectual, such as “labour” and “capital”, Atkinson writes in the more measured tradition of the British empiricist. The conclusions, however, are just as disruptive.

Atkinson does not want a revolution, nor even to eliminate all economic distinction incrementally, as reformist socialists such as Bernard Shaw once hoped to do. After a lifetime of analysing inequality, the Atkinson ambition is merely to narrow the gap in the UK to where it stood when he started. It ought to be a realisable dream – it is a reality in egalitarian corners of northern Europe – but after an election in which Britain rejected moderate social democracy in favour of an inequality-indifferent Conservative government, it may seem impossible.

Atkinson demonstrates how – without violating any fiscal constraints – different political choices could start to make a difference. To give some examples, he would overhaul the absurd council tax, which charges big homes proportionally less than small ones, and on the strength of the depressed valuations of 1991. New Labour and the coalition both cravenly refused to update these to reflect the windfall that the property market has gifted to homeowners, in London especially; chancellor Atkinson would put that right.

Where George Osborne pledges to cut inheritance tax Atkinson would instead recast it, replacing a leaky levy on the estates of the dead with a harder-to-dodge charge covering large gifts during life, as well as posthumous bequests. He would sharply increase benefits and reduce means-testing. That would cost serious money, of course, but – if the politics allowed for it – this would not be a problem, because a newly progressive income tax, rising in steps to a top rate of 65%, would bring in serious revenues. To those of us who grew up in Thatcher’s shadow, this may sound like impossiblist stuff, but Atkinson demonstrates that the constraints are purely political, not economic. One of his many scholarly assaults on the conventional wisdom exposes the research that Osborne relied on in cutting the 50p rate. Atkinson details how this study, which concluded that the “super-tax” wasn’t raising any money, had dubiously assumed that top incomes were all salaries rather than self-employed fees or anything else, and further that they came about solely because of individual effort. If inflated top salaries are instead, to any degree, awarded at the expense of other people, then higher top tax rates are justified.

Wild as the redistributive menu will seem to the average MP, it transpires that swallowing everything on it would only take Britain halfway back to the 1970s in inequality terms. At this point, lesser spirits would give up, and retreat from a problem that is looking too difficult. Atkinson, however, continues, moving beyond taxes and benefits. This means the book gets more difficult, but also more interesting. The other half of the inequality-reducing work has to be done through policies on competition, technology and jobs, all fields in which the presumption has long been that the market knows best.

A dash of industrial democracy could help, particularly in relation to top pay. So, too, would new rules on corporate mergers. They should no longer be nodded through on the assumption that lower prices for consumers were the only good: the prospects for jobs should become a consideration, too. And instead of passively submitting to an unstoppable tide of technology, public policy should take some responsibility for the direction of its flow.

This is the sort of meddling from which today’s orthodox thinkers run a mile. Their point of departure – first in university textbooks, and then in the analysis that economics graduates go on to perform for government departments – is a complete and perfectly competitive market, which hums along beautifully if left to itself.

Atkinson is a first-rate economist who long ago mastered the orthodoxy, and so is well‑placed to take it to bits. Patiently, he explains why excessive profits may not be competed away, and why laissez-faire cannot be relied on to get the most out of every resource. Some of the specific quibbles and caveats with the orthodoxy are familiar, but I’ve never seen them all pulled together in this way before. He demonstrates that the fantasy world of perfect competition is not the right starting point for analysing reality. That insight discourages the lazy intellectual imperialism that Zoe Williams refers to in her book, Get it Together,when she describes “some idiot with a PPE degree who can’t remember anything except that he knows everything, and nobody else can understand”. If we don’t want such idiots running the country, we need to assault the intellectual edifice on which they stand.

Atkinson also has a keen sense of history. He explains how anti-trust laws in the US, nowadays narrowly justified in efficiency terms, were originally born out of concerns about fairness. He highlights, too, how the course of industrial technology has often been set by the planners’ guiding hand. All this helps him break out of the frighteningly narrow terrain that economists concede to public policy. In a world where City shenanigans are more in evidence than perfect competition, all sorts of interventions could help to reduce inequality – union activity, technology policy, moves to cut corporate companies down to size.

“I don’t care who writes a nation’s laws – or crafts its advanced treatises – if I can write its economics textbooks,” said Paul Samuelson, the man who wrote the most famous textbook of the lot (Economics: An Introductory Analysis, 1948). At one point, Atkinson explains that he is not writing a textbook, but perhaps that’s what he should do next. For as well as demonstrating that something could, after all, be done about the wealth gap, he also shows the urgency of a new economics, one based in the real world, instead of marketopia.

Dead Aid: Why Aid is not working

By Dambisa Moyo.

Review By Jane Wales.

As the global financial crisis unfolds, those least responsible—our world’s poor—will be most affected. Many have called upon President Obama to uphold his campaign commitment to double foreign assistance. But Dambisa Moyo’s book, Dead Aid, challenges us to think again. Although we can all agree that ending poverty is an urgent necessity, there appears to be increasing disagreement about the best way to achieve that goal.

Born and raised in Lusaka, Zambia, Moyo has spent the past eight years at Goldman Sachs as head of economic research and strategy for sub-Saharan Africa, and before that as a consultant at the World Bank. With a PhD in economics from Oxford University and a master’s degree from Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, she is more than qualified to tackle this subject.

In Dead Aid, Moyo comes out with guns blazing against the aid industry—calling it not just ineffective, but “malignant.” Despite more than $1 trillion in development aid given to Africa in the past 50 years, she argues that aid has failed to deliver sustainable economic growth and poverty reduction—and has actually made the continent worse off . To remedy this, Moyo presents a road map for Africa to wean itself of aid over the next five years and offers a menu of alternative means of financing development.

Moyo opens her case by writing, “Between 1970 and 1998, when aid flows to Africa were at their peak, poverty in Africa rose from 11 percent to a staggering 66 percent.” Today, Africa is the only continent where life expectancy is less than age 60. Sub-Saharan Africa remains the poorest region in the world, where literacy, health, and other social indicators have plummeted since the 1970s.

Pulling us through a quick history of aid, Moyo covers the many ways its intent and structure have been influenced by world events. She systematically challenges assumptions about the efficacy of the Marshall Plan, International Development Association graduates, and “conditionalities” that require adherence to prescribed economic policies. “By thwarting accountability mechanisms, encouraging rent-seeking behavior, siphoning away talent, and removing pressures reform inefficient policies and institutions,” aid guarantees that social capital remains weak and countries poor. And Moyo’s list of aid’s sins goes on—including the crowding out of domestic exports and raising the stakes for conflict.

So what does Moyo propose we do? In her own version of shock therapy, she asks, “What if, one by one, African countries each received a phone call, telling them that in exactly five years the aid taps would be shut off —permanently?” The shock would force them to create a new economic plan that phases in alternative financing mechanisms as aid is phased out, she argues. These new financing mechanisms should include increased trade (particularly among African nations and with emerging markets like China, India, and Brazil), foreign direct investment, entrance into international capital markets, and increased domestic savings through remittances and microfinance. The end goal is to phase reliance on aid down to 5 percent or less within five years.

Sound impossible? Moyo doesn’t think so. Implementing this plan will be “dead easy,” she claims, but will require political will. This political will, Moyo argues, must be rallied by Western activists, for they are the only ones with the ability and the incentive to drive change. “It is, after all, their money being poured down the drain.” She is not the first to call for a move away from aid dependency—although she may be the fiercest.

Moyo has only proven correlation, not causation, and although we can’t be sure how her prescriptions would hold up in the face of a global recession, she challenges us to think before we act. Moyo expands the boundaries of the development conversation—one that has become both more vibrant and more nuanced in recent months. Those of us rethinking aid can all agree that the time has come for deeper and more direct involvement of Africans in setting their own development course. As the African proverb goes: “The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second-best time is now.” Let us not waste any more time. Africa’s moment, and our moment, is now.

The role of religion in African development

Religion in Africa.

The last 60 years have witnessed the accession to sovereign status of dozens of former colonial territories and the birth of the modern development enterprise, but also a rapid secularisation of Western European societies especially. Yet, at the start of a new century, religion seems set to be a major force in international affairs in the world for the foreseeable future. Its public role can no longer be ignored.

Religion is of great importance in Africa in that most people engage in some form of religious practice from time to time, and many profess membership of some formal religious organisation, traditional, Muslim, Christian or otherwise. Many Africans voluntarily associate themselves with religious networks, which they use for a variety of purposes - social, economic and even political - that go beyond the strictly religious aspect. But what does 'religion' mean in the context of Africa? The evidence suggests that most of the continent's people are religious inasmuch as they believe in the existence of an invisible world, distinct but not separate from the visible world, that is inhabited by spiritual beings or forces with which they can communicate and which they perceive to have an influence on their daily lives. Religious ideas typically govern relationships of people with a perceived spirit world. In effect, this idiom can govern relations both of one person to another, or of one person to a community, but also of people to the land they cultivate.

Donor agencies could certainly make greater efforts to consider the role of religion in Africa through relatively simple means. It has sometimes been suggested, for example,

that foreign embassies in Africa may be well advised to appoint religion attachés charged with the task of observing religious life, much as they have defence attachés at present. This does not in any way imply that observers must themselves be religious practitioners or believers, but suggests only that they should have proper knowledge of religious organisations and networks in Africa of all descriptions and inform themselves of the type of thinking that underlies them. They need to monitor and understand processes of religious change, such as those that have given rise to evangelical Christian communities, the development of reformed Islamist organisations, and the revival of neo-traditional groups such as initiation societies.

There are very active debates within religious communities of all types in Africa including, for example, in those Muslim groups and Islamic networks that cause concern to Western countries on security grounds, concerning the proper interpretations of their religious duty. Calls are often heard for inter-religious dialogue, and it is hard to dispute the usefulness of this, but at the same time we doubt whether inter-religious dialogue is sufficient to diffuse religious tensions where such exist. First, people who are inclined to inter-religious dialogue are probably also those individuals who are the least inclined to take up weapons in support of their faith, and therefore are the least in need of persuasion towards the way of peace and coexistence. Second, many of the religious debates that are most threatening to peace or human rights actually take place within religious communities. Hence, we argue that inter-religious dialogue may be less urgent than intra-religious dialogue. Such intra-religious dialogues are worthy of far more attention than they actually receive from development experts. As in other aspects of religion, people or institutions interested in development need in the first instance to inform themselves of the debates that are taking place in particular contexts or in individual countries and to acquaint themselves with some of the key actors. Only then may they be able, in consultation with local partners, to find ways of encouraging dialogue in the interests of human development.

Using religion for development

We would emphasise that an appreciation that religion is a resource for development does not mean that policy-makers can simply add religion or religious institutions to the range of policy instruments at their disposal, other than in rather exceptional cases. However, given that proviso, it is certainly possible to identify specific sectors in which religion could play a positive role in development. Below, we briefly consider a number of such fields, providing brief examples:

a. Conflict prevention and peacebuilding

Peace is a precondition for human development. Religious ideas of various provenance - indigenous religions as well as world religions - play an important role in legitimising or discouraging violence. Increasingly, large-scale violence in Africa is associated with social conflicts. In many such conflicts fighters seek medicines or various objects or substances that they believe will make them effective in battle or will defend them against injury, and the persons who dispense such medicines exercise influence over the fighters. In some cases, this can take on a clear institutional form. In Sierra Leone, for example, the kamajor militia was organised along the lines of an initiation society and was associated with the most influential traditional initiation society in the country, Poro. Similar developments have been witnessed in Côte d'Ivoire, Liberia, Nigeria and elsewhere.

Our argument here is not that quasi-military movements such as these - often responsible for appalling human rights abuses - are to be encouraged. Rather, the argument we are making is that the spiritual aspects of such movements must be understood if the movements themselves are to be understood. Moreover, the institutional affiliations of such movements could provide a means of helping to regulate such movements in future.

Regarding the establishment of unofficial militias such as the kamajors (although the latter eventually received a degree of official licence), it is notable that there are now many African countries where state security forces have lost any realistic claim to a national monopoly of violence, and where locally organised vigilantes or similar groups proliferate and sometimes receive a degree of official sanction. Such local groups almost invariably have a religious dimension (in the sense that we have defined religion: see above), like the kamajors who are thought be protected by powerful spiritual forces. It seems quite likely that in time, locally-established forces will come to be considered in some shape or form as a substitute for fully effective centrally organised police and military forces, that are unable to fulfil their formal mandate in so many African countries. The kamajors, for example, were part of an officially- recognised Civil Defence Force that was instituted by the Sierra Leonean government in 1997: indeed, the recognition of this new force was one of the factors that led to a coup by sections of the armed forces in May of that year. Another example is the Bakassi Boys, a vigilante group originally established by market-traders in south- eastern Nigeria in the late 1990s to protect themselves and their communities against the bands of armed robbers that were then terrorising their areas. The Bakassi Boys were subsequently adopted as part of the official security forces, notably in Anambra State, with the result that they soon degenerated into a personal militia at the service of local politicians, and were responsible for a series of political murders.

Neither the kamajors of Sierra Leone nor the Bakassi Boys of Nigeria, then, are examples to be emulated. But they are both instances of local militias that have at some point in their existence enjoyed a real popularity in some communities, with ties to local stakeholders. In both cases also their cooptation by powerful politicians has reduced their ability genuinely to defend local communities. Thinking is urgently required on whether or how local militias may be made responsible to local stakeholders and how they may coexist with national security institutions in a relationship strong enough to avoid the risk of creating a host of local fiefdoms.

By the same token, the end of armed conflict is often accompanied by ritual action to 'cleanse' fighters from the pollution of bloodshed. This is done through traditional rituals in many countries, but also takes the form of the experience of 'born-again' Christianity, for example. The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, led by an Anglican archbishop and closely associated with the country's faith communities, was also based on the idea that long-term reconciliation depends crucially on religious notions of reconciliation and healing, even in the absence of formal justice. Although the TRC has been criticised in South Africa itself, its ultimate success or failure will only become apparent with the passage of time. In the meantime it has been widely imitated. Truth commissions based more or less on the South African model have been created in Nigeria, Ghana and Sierra Leone, where they had a mixed record, and have been mooted in many other African countries. These examples suggest that truth commissions are far from a panacea. First, the right political conditions have to exist if they are to have any chance of genuinely helping to reconcile conflicts. Second, even if the conditions are ripe, each country needs to think out the form and style of its own commission rather than imitating the South African exemplar. In Sierra Leone, the establishment of a truth commission simultaneous with a special court posed considerable problems for the institutions of transitional justice. Finally, establishing a reasonably successful truth and reconciliation commission requires considerable finance and the maintenance of an efficient secretariat with real research capacity. In many cases these will require input from external sources.

b. Wealth creation and production

It is widely acknowledged that religious ideas played an important part in the development of capitalism in the history of Europe, not always directly, but in influencing people's thinking on the legitimacy of wealth and on the moral value of saving or investing, for example. Although it is by no means inevitable that other continents will develop along the same lines, this does suggest the significance of current religious ideas such as the widespread existence of the so-called 'prosperity gospel' in Africa, or the importance of certain religious networks, like the Mourides of Senegal, in creating wealth. Development workers would be advised to monitor such ideas and the groups espousing them closely, with a view to identifying opportunities for policies aimed at wealth creation or enhancement.

Control of land and the role of religion in expressing people's ideas about the proper use and ownership of land is closely connected to what remains Africa's most fundamental economic activity: agriculture. At present, some 66 per cent of people south of the Sahara live in rural areas, and many of these derive their living in part from agriculture, directly or indirectly. In many parts of the continent, traditional forms of landholding preclude women from ownership of land or even place taboos on the ownership of agricultural implements by women, despite the key role they often play in cultivation. There are also many examples of traditional chiefs having the power to grant land while retaining the right to recall its use – a power that is open to abuse. In some cases, particular ethnic groups may traditionally be forbidden from owning land but may enjoy usufruct rights only. (Such a principle has been associated with violent conflicts in Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire.) All of these are examples of traditional ideas concerning landholding that may offend against current ideas concerning universal human rights and also be in contradiction with Western-style systems of individual land tenure guaranteed by law. Hence it is no solution to argue for the preponderance of traditional forms over modern ones inspired by Western models. Rather, what is required is to consider what elements of traditional systems might usefully be adapted for current purposes in the light of contemporary ideas of justice and human rights as well as the demands of agricultural efficiency.

Although it is risky to generalise about a sub-continent as large and diverse as sub- Saharan Africa, it is clear that many countries will not emerge as industrial producers or with internationally competitive service sectors in the foreseeable future. It remains as important as ever that agriculture be encouraged. Enormous obstacles exist to the expansion of agriculture in Africa, ranging from the subsidies paid by governments in the European Union and the USA to their own farmers, making African products uncompetitive, to the phenomenon of 'urban bias' inherent in the policies of the many African governments that, for political reasons, prefer to favour urban sectors at the expense of rural-dwellers.

However, even if such issues are addressed, it is also important to integrate into agricultural policy crucial elements of culture and religion that are associated with the prosperity of agricultural societies. For example, in many places, policies aimed at encouraging individual legal title to ownership of land may need to be modified to take account of traditional ideas concerning land ownership, in which land is typically viewed as being owned by a community of people by virtue of their relation with ancestor spirits or with spirits of the earth, frequently clash with systems of individual title recognised by the state. Much more research is necessary on how land tenure can be protected by state law while also acknowledging the importance of traditional ideas concerning community or social rights to land that often have a reflection in religious ideas.

c. Governance

The possible role of religiously-based networks in Africa's future governance extends far beyond the fields of security and the law. It is striking, for example, that revenue collection is one of the main problems facing states in Africa, which typically have budget deficits and which are unduly reliant for their revenue on dues levied on import- export trade, or on external sources of funding, including aid. Most have a poor record in the collection of taxes from their own populations, making states unhealthily dependent on foreign sources of finance rather than on their own populations. The relationship between a state and its domestic tax-payers is an important element of real citizenship. Meanwhile, many religious networks in Africa survive largely or entirely from tithes or other monies donated by their members: in effect, their ability to tax their own members is testimony of the success of many religious organisations in developing a close bond with their adherents, and a degree of accountability to them, in contrast to the problems of citizenship faced by African states in general.

The question may be asked whether, in the considerable number of African countries where the state exercises little real authority outside the main cities or a handful of nodal points, and where states have very little ability to tax their nominal citizens, religious networks will not assume some of the functions of government in future.

In short, in the considerable number of African states in which government through efficient, centrally-controlled bureaucracies is clearly inadequate to ensure the country's security, or to raise sufficient resources through taxation as to fund the reproduction of the state itself, or to ensure a minimum level of welfare for the country's people, non- state organisations are destined to play a much greater role in future. Many of the best- rooted non-state organisations have an explicit religious basis, whether it is in the form of educational establishments run by churches or by Muslim networks or in vigilante movements underpinned by traditional initiation societies. In future, state and religious organisations may be called upon to play a complementary role in the governance of society.

On closer inspection it is also apparent that many Africans in fact debate key political questions, including the fundamental legitimacy of their own governments, in religious or spiritual terms. This is apparent from the popular literature, videos and other published material that circulates all over the continent and that is consumed and discussed widely. Many such publications discuss current problems of governance, crime and morality, typically viewed as manifestations or conceptions of evil. In what might be termed a spirit idiom, they express concern with what in development jargon is termed poor governance. Ultimately, this is having a great effect on governments whose fundamental institutions, having been founded in the colonial period by Europeans who had a view of the proper form of governance based on Europe's own history, risk being considered of dubious legitimacy.

*Stephen Ellis is a senior researcher at the Afrika-studiecentrum, Leiden.

*Gerrie ter Haar is professor of Religion, Human Rights and Social Change at the Institute of Social Studies, The Hague.

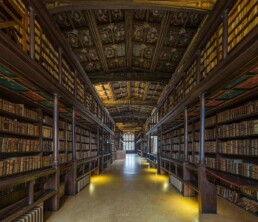

**Image: Courtesy of National Geographic.

Globalization and International Civil Society: Are Human Rights still the Exclusive Preserve of States?

Introduction

The defeat of Germany in the Second World War, and the subsequent birth of the United Nations in 1945 ushered in the modern human rights regime. Prior to this post-war era, human rights was not a salient feature in the parlance of international law, and for good reason; nation-states were guided by the civility of the ‘good-neighbor,’ which meant that ‘good-neighbors’ do not interfere or unilaterally intervene in matters of purely domestic character outside their territorial competence. Formally, the ‘good-neighbor’ ethos came under the umbrella of state sovereignty, and to a large extent, continued to dictate how states dealt with one another even after the advent of the UN, and the consequence on human rights movement remained unchanged: States continued to regard human rights as domestic matters that should be dealt with domestically, any outside intervention was considered ‘bad form’ and an affront to the norm of state sovereignty. That was then!

The United Nations, after a few decades of drafting conventions, covenants, protocols, and norm setting, has managed to ‘internationalize’ human rights, at least in normative terms. The implication of this achievement is enormous; for, it means that for the first time in human history, human rights has acquired a certain ‘universality’, and in so doing shed its overly confining character of domesticity. Since every state has signed at least one human rights convention or treaty, States can no longer legitimately use the shield of State sovereignty in cases of gross human rights abuses;1 human rights is now an international concern! On the same point, Buergenthal was sufficiently succinct: “Despite their vagueness, the human rights provisions of the UN Charter have had a number of important consequences. First, the UN Charter “internationalized” human rights. That is to say, by adhering to the Charter, which is a multilateral treaty, the state parties recognized that the human rights referred to in it are objects of international concern and, to that extent, no longer within their exclusive domestic jurisdiction.”2 But while the UN has a lot to do with this transformation of rights, other players in the field were just as effective. More on these other players in due course.

The thrust of this essay is that the confluence of rapid globalization of world affairs, the active participation of NGOs and international civil society in human rights discuss has hastened the internationalization of human rights, and as a consequence, the norm of state sovereignty in matters of human rights is rapidly losing significance, and with time, will ultimately become redundant; a faith accompli, if you will. While NGOs, and international civil society have been extraordinarily effective, in conjunction with the various organs of the UN, in ‘universalizing’ human rights in recent decades, my principal focus in this essay will be on the contributions in this regard by the modern phenomenon of ‘globalization’ masterminded by international civil society. In the following pages I will highlight the fact that globalization impacts all aspects of human rights, particularly in developing nations, and that such impacts are very different for different rights.

Globalization and Human Rights

Globalization, spurred by advancement in technology, may be defined as the enhancement of intimacy in the international community. The range of this intimacy is varied, and includes such staples of world affairs as economics, politics, culture, law, and technology. These aspects of world affairs are not new; what is remarkably recent, however, is how modern civil society has used science and technology to redefine, and drive world events. This is particularly true in the area of telecommunication; in the last decade alone, the world has suddenly become a ‘global village’ where consumption of information is almost instantaneous, and international trade and transactions are now akin to shopping in the ‘neighborhood.’ This remarkable transformation of the order of things has everlastingly changed the roles of political and economic actors on the world stage; gone are the days when governments jealously clung to the levers of information machineries, and can operate in near total secrecy; gone also are the days when governments, through their domestic policies, controlled the bulk of economic activities within its boundaries. As national boundaries become so porous as to become redundant, so too will the notion of state sovereignty.

But this is not to suggest that the state has become an ephemeral institution; very much to the contrary, it simply means that in the light of globalization, the state will need to redefine itself and its role in a modern society empowered and enlightened by advancing technology. It also means that the means by which it once controlled its domestic affairs have become marginalized. And herein lies the implication for human rights.

Civil and political Rights

Transnational corporations and institutions principally formed and controlled by international civil society have made remarkable use of advancing technology in the production and distribution of goods and services. The discovery and exploitation of new markets have made it possible for these transnational organizations to reach deep into the recesses of world economy, and with such leverage are able to influence or dictate outcomes in their dealings with national governments. This is particularly true in developing countries where economic activities are severely depressed, and economic might is revered. For many socially conscious transnational corporations, global power has meant a chance to advance the cause of basic human rights. They have achieved this by insisting that national governments abide by the rule of law, uphold the civil and political rights of its citizens, stop the use of torture and other inhumane treatment of political prisons, and hold free and fair democratic elections. While a difficult pill to swallow, governments notorious for their gross abuses of human rights have been known to acquiesce or risk the loss of significant economic aid. To the extent that transnationals are able to insist on these requirements, states can no longer claim exclusive jurisdiction over human rights.

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

By insisting that governments in countries where their productive activities are engaged commit to the protection of basic human rights, transnational corporations have managed to advance the universality of only certain kinds of rights, specifically civil and political rights. These rights are by their very nature more malleable to the kind of pressures that transnationals can bring to bear on States. Unfortunately, however, the same pressures that have the potential to protect civil and political rights in developing countries can have the opposite effect on the economic, social and cultural rights of the indigenous people of the state. A two-edged sword indeed; very painful to push-in, and just as painful to pullout! Examples abound!

The essence of markets, and almost invariably that of transnational firms, is the effective allocation of resources with a view to profit maximization. Any other human sentiments or motives are necessarily secondary. With this objective in mind, entrepreneurs seek out new markets to develop and exploit, but in order to maximize their profit potential, they first must minimize their overall cost of production. It is in the pursuit of this objective that the goals of transnationals come into conflict with other kinds of human rights. In order to minimize cost, many transnationals form an unholy alliance with government officials (Shell in Nigeria),3 and this enables the exploitation of the natives by paying non-living wages, buying vital mineral rights at give away prices, and subjecting their indigenous workers to horrible working environments. But this is the good part of the entire experience; it gets worse! The more sophisticated transnationals soon discover that it is cheaper to dump their untreated chemical wastes in developing countries at a fraction of what it will cost to dispose of them in their country of origin. And so, for the promise of a non-living wage, and the opportunity to consume western products, natives are economically exploited, and exposed to toxic wastes. Thus, if they do not die from poverty-induced complications, poisons from toxic wastes will get them!

A more insidious form of exploitation or abuse of economic and social rights of the natives is not quite as detrimental, but nonetheless potent. This comes by way of bureaucratic corruption; corruption of public officials by transnationals in order to expedite business activities that would have taken much longer than the ‘Captains of industries’ are willing to bear. The end result is that bureaucratic corruption becomes rampant and endemic in these developing countries with the predictable consequences of graft, outright theft of public funds, and massive misallocation of the countries’ vital resources. A recount of a personal experience by the author will help put this phenomenon in the proper perspective.

Globalization and Bureaucratic Corruption in Sub-Saharan Africa: A personal Experience

At the outset, it will be helpful to put in proper context what I mean by bureaucratic corruption; and define the geographic parameters of my analysis. For expositional simplicity, I will focus on the incidence of bureaucratic corruption in Sub-Saharan Africa, and the attendant consequences on socio-economic development. While bureaucratic corruption, to be defined shortly, is not an exclusive domain of black Africa,4 it is however, one of the enduring peculiarities of the sub-continent that has perennially subdued economic and technological development.

Bureaucratic corruption, in its popular sense, is the misuse of the power of public office for personal gain in breach of laws that govern public servants and moral principles. In its basic form, it takes place when a government official demands and accepts bribes or kickbacks in performance of normal duties called for by the office. Bribery, which can be direct cash payments, gifts, or the promise of reciprocity in future transactions, is usually paid either: (1) to gain access to scarce government services, or (2) to avoid the cost of a government service. Bureaucratic corruption can, of course, be found in developed as well as in developing nations;5 however, its consequences are particularly more troublesome for developing nations with inadequate or poorly formed socio-political structures and weak judicial institutions. Because of its distortionary effects on resource allocation, entire economies are often severely weakened and debased as important decisions are guided not by prudent public policy but by ulterior agenda.

The author recalls two incidents that have striking similarities but differ only in degree. As a young graduate student in the early 1980s, I was stopped by the police for a traffic infraction at the early hours of a Saturday morning. After the usual preliminaries of asking for my driver’s license, and registration, he inquired about my nationality, where I was headed at that time of the morning, and what was I willing to do to discharge my immediate predicament. Sensing the tone of the inquiry, I tendered the customary apologies, and wondered out loud if it would be possible to make a charitable contribution to the ‘police fund.’ He said I could, and would be glad to pass-on my contribution to the ‘fund’. Ten dollars changed hands, and I was given the standard admonition to drive safely, and was allowed to leave. No official citation was issued, and neither was a receipt issued for my ‘donation.’ This occurred in Chicago.

Ten years later, I shipped forty units of power generators to Nigeria for a project. The transatlantic shipment took four weeks; however, it took another five weeks to get the goods through Nigerian ports authorities. First, the goods had to be inspected and cleared by the attending Customs officer. The problem, however, was how to locate him. But at last it took an inordinate expenditure in time and financial resources to finally meet with him; mainly because each time my clearing agent came calling he was dutifully informed by low-ranking officials that he was not in the office. In other words, he needed to be persuaded, and that was a clue that more money was being demanded. After a week, and having disbursed approximately US$700 to his assistants, the official papers were suddenly produced, completed, and signed. Meanwhile, the container of goods was cleared and uninspected. The goods must now be further inspected and cleared by the navy, and national security agents. The same ordeal was exacted on my agent and me; the only variation here was that we now had the opportunity to haggle and bargain on the amount of bribe to be paid.

Exactly five weeks after the goods arrived in Nigeria, we were given complete clearance to remove them from the port. Our celebration was short-lived; because in less than an hour after leaving the port, we were stopped by the police for inspection. Two hundred US dollars equivalent were demanded and paid; again, as in other instances no actual inspection was made. Within five miles of this ‘inspection’ was another police check- point. Realizing that we had fifteen more miles to travel, it became necessary to pay and retain this second group of police officers as escorts. Needless to say, the original objective of the project was thoroughly frustrated, and ultimately suspended. The point of this narrative is that in many instances, the difference in the incidents of corruption in developed as well as in developing countries is a matter of degree. The differential economic impact, however, is remarkably significant. Thus, with the economy thoroughly debased, economic, social, and cultural rights become non-issues.

Conclusion

That modern human rights movement has benefited from the globalization of world affairs is unquestionable; that globalization has also marginalized certain kinds of human rights in underdeveloped countries is not in doubt. The issue now is whether on balance globalization has done more to advance the goals of international human rights, and the answer will be a qualified ‘yes.’ For one, it has empowered the once powerless through the delivery of near instantaneous information, and knowledge; this has enabled citizens of the world to question, challenge, and demand reform from their governments. International civil society, through entrepreneurial endeavors, has compelled governments in developing countries to institute democratic reforms that protect basic human rights even though some of their activities continue to have the opposite effect. NGOs have also played significant roles in internationalizing human rights. Through publicity, advocacy, and on-site inspections, International NGOs such as Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch, continue to educate the world on human rights atrocities throughout the globe, and ‘shame’ governments into reform, while at the same time empowering the oppressed through concerted campaigns and legal assistance.

The end result of all this is that States can no longer consider human rights as purely domestic matters; States must now contend with the international community when gross violations of rights occur within their boundaries. “At least,” says David Forsythe, “it now can be said that states have accepted a number of new legal obligations and that numerous ‘cases’ exist which can be used as ‘precedents’ should actors choose to do so in pursuit of human rights values.”6 And I am sure they will; it is just a matter of time!

1 See generally Robert McCorquodale with Richard Fairbrother, Globalization and Human Rights; Human Rights Quarterly, 21.3 (1999), 73-766.

2 See Thomas Buergenthal, International Human Rights, 2nd. Edit., West Group, 1995, P. 35-41.

3 See The Economist, May 12, 2003

4 See Braibanti, Ralph, In Monday Ekpo’s Bureaucratic Corruption in Sub-Saharan Africa: “Toward a Search for Causes and Consequences”, University Press of America, 1979.

5 See De Soto, Hernando, The Other Path. New York: Harper and Row, 1989.

6 See David Forsythe, The United Nations and Human Rights, 1945-1985.

Poverty Traps

Reviewed by M. Krul.

"Poverty Traps" is a collection of research papers on the subject of, well, poverty traps, edited by Bowles, Durlauf and Hoff. Each of these are known for their use of orthodox methodology against the economic orthodoxy itself in substantial terms, and that is also the approach taken in this book. The book consists of a small number of fairly large essays, more or less thematically organized, which seek to explain how poverty traps come into being and how they are reproduced. In this context, a poverty trap is defined as a less-than-optimal solution which is nonetheless an equilibrium, where there also exists an optimal (or at least better) equilibrium.

By far the best part of the book is Part II, which discusses institutions and how they serve to create and reinforce such poverty traps. Engerman & Sokoloff have a fascinating article on the importance of land policies and the crops produced in different parts of the American continent since colonization as a cause of the strong discrepancies in wealth between the North and the Middle/South. Mehlum, Moene and Torvik use classic orthodox methods to show that in African nations, there can be a poverty trap as a result of organized crime, militias etc. being parasites on productive companies, where they keep each other balanced at a suboptimal level. Hoff & Sen have an excellent essay on the problems with kin systems in Africa and Asia and the way in which they can inhibit modernization. And finally Samuel Bowles himself uses a game theoretical mathematical approach to show how suboptimal social conventions can be very hard to change in circumstances of great inequality, despite the amount of people benefiting from the conventions are very few in proportion to those negatively affected. Also of great interest is the first essay in Part III, by Steven Durlauf, which deals with how group pressure and neighborhood influences can account for the continuing bad situation in very black areas of the United States.

What is frustrating about this book is that the authors are so clearly constrained by the faux 'rigor' of orthodox economics in fully developing their case. Reading between the lines this seems to have been the case for some of the authors themselves as well, but it will certainly strike any reader that about half the book is devoted to mathematically describing and modelling arguments which are perfectly sensible and easily understood in just their regular written form. The added value of making a model with a host of unworldly and absurd assumptions to prove a particular point that could just as easily be proven in terms of "people tend to behave like X under Y circumstances, because of social cause Z" is unclear, and it is one of the many unfortunate products of the academic atmosphere in the field of economics. What passes for 'rigor' is in reality a useless and failed attempt to imitate physics and to impress the noninitiated. It is a pity that this draws smart minds, as the cases of Moene (associated with 'Analytical Marxism') and Bowles (the leader in behavioral economics) show - both are approaches which want to do good social science, uninhibited by liberal dogma, but which are hampered by their own insistence on methodological orthodoxy. This is a good scientific work, but its own methodology hinders it.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

African Economic Development

BY Steve Langdon, Archibald R.M. Ritter, Yiagadeesen Samy.

Sub-Saharan Africa is at a turning point. The barriers to economic growth seen in the 1980-2000 era are disappearing and new optimism is spreading. However, difficult goals of eliminating poverty, achieving equity and overcoming environmental threats continue. This much-needed and insightful textbook has been written to help us understand this combination of emerging improvements and significant challenges.

Opening with an analysis of the main theories relating to development in Sub-Saharan Africa, the book explores all the key issues, including:

Human development;Rapid urbanization;Structural and gender dimensions;Sustainable development and environmental issues; and Africa’s role in the world economy.

The authors use economic tools and concepts throughout, in a way that makes them accessible to students without an economics background. Readers are also aided by a wide range of case studies, on-the-ground examples and statistical information, which provide a detailed analysis of each topic. This text is also accompanied by a companion website, featuring additional sources for students and instructors.

African Economic Development is a clear and comprehensive textbook suitable for courses on African economic development, development economics, African studies and development studies.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Black Lives Matter Protests in Africa Shine Light on Local Police Brutality

John Campbell.*

The African media has closely followed the Black Lives Matter protests in the United States, almost always in solidarity with the protesters. Especially among African human rights groups, the American focus on police brutality resonates strongly. While generalization is risky about a continent with more than fifty states and one billion people, it can be said that for most Africans, the policeman is not your friend. The popular perception is that police brutality is the norm.

Police use of excessive force is an old song in Africa, and reform is difficult. Police forces tend to have been established by the former colonial powers, and they are national—a gendarmerie—rather than local. They are often poorly trained and paid; many resort to petty corruption simply to feed their families. Too often their culture is oriented toward protecting the state, just as it was during colonial rule, rather than serving the public. The elites that control and benefit from the state often dismiss cases of abuse and are slow to institute meaningful reform.

In many African countries, the police are one element in a system of institutional underdevelopment. Where the rule of law is feeble, courts are often corrupt, and prison conditions can be unspeakable, people will take justice into their own hands. There are reports of mobs lynching an alleged thief caught stealing in a city market, for example. Hence, too often the police function as a weak, under-resourced occupying power, too ready to resort to excessive force.

Hence, meaningful police reform may require the overhaul of the entire legal and judicial system and a fundamental, positive realignment of governments with the people they ought to serve. Such a reform program is not so simple or easy on a continent in the midst of a pandemic and one in which the quality of political leadership is often poor.

*John Campbell is Ralph Bunche Senior Fellow on Africa, Cfr

**Courtesy of Council on Foreign Relations

Why Norway is not panicking about the oil price collapse

Paul Buvarp.

Norway’s petroleum sector is its most important industry. The petroleum sector accounts for 21.5% of its GDP, and almost half (48.9%) of total exports. In 2013 Norway was ranked the 15th-largest oil producer, and the 11th-largest oil exporter in the world. It is also the biggest oil producer in western Europe.

Oil is therefore regarded as a vital national resource and is the backbone of the Norwegian economy, though just like in the UK, its best years are in the past. Production levels have been dropping since the turn of the century, peaking at 3.5m barrels per day in 2001 to less than 1.9m in 2014.

Norway is not a member of theOrganisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries(OPEC), and in principle it sets prices based on the current market. But with OPEC having a virtual monopoly on global pricing, Norway in effect remains subject to the cartel’s pricing decisions. Norway is thus vulnerable to the volatility in oil pricing, and with regard to the structure of the sector and its role in the Norwegian economy, this vulnerability is extended throughout the society as a whole.

With the unsettling and dramatic slide in oil prices since June 2014, Norway has of course been substantially affected. Two months ago, Statistics Norway cut this year’s GDP forecast from 2.1% to 1% on the back of lower prices. A few days later the central bank unexpectedly cut interest rates to an all-time low of 1.25% to help stimulate the economy. Some 12,000 jobs are being cut as the oil industry pares back about 10% of its workforce, and there are fears that nearly 30,000 more could follow.

Statoil and the oil industry

Oil in Norway is dominated by Statoil, the largely state-owned oil company, which controls about 70% of the country’s petroleum production. It reported staggering losses in the third and fourth quarter of 2014 that were partly the result of the lower oil price – the company’s first loss since it listed on the stock market in 2001. Its share price is also down about a quarter on last summer. The majority of job losses in the sector are due to cost-cutting and reductions to capital expenditure that are aimed at steadying the ship.

Experts regard the low price as a difficulty mainly for the profitability of specific expansion projects, meaning that they could be postponed or even cancelled. High oil prices have made certain investments possible, which are now in trouble. For instance Statoil has held off on decisions on a US$6bn investment into the Snorre field in the North Sea and the huge Johan Castberg field in the Barents Sea.

Consultancy Wood Mackenzie is forecasting that petroleum investments in Norwegian waters will be down 25% this year, with foreseeable cuts in subsequent years too. There is at least one consolation for the industry: the huge Johan Sverdrup field, which is due to begin output in 2019, appears to be viable at prices beneath US$40 a barrel.

The Norwegian government also recently announced that by way of stimulus it would award a tranche of new oil and gas drilling licences next year, including opening up the first new area for exploration since the 1990s. It has also called for the sector to adapt, suggesting that the height of exploration and development has been achieved for oil exploitation, and the sector must now consolidate its position. However, so far there have been few specifics.

The national budget

Unlike in the UK, the main narrative in the Norwegian media is not about cutting producer taxes but worry about the state failing to obtain its expected revenue as outlined in the country’s budget. Some experts believe that if the trend continues the actual revenue collected for the pension fund this year could be as low as half of what was budgeted, which would doubtless be a blow.

Last month, Norwegian prime minister Erna Solberg and finance minister Siv Jensen held a press conference on the situation, underlining that the government is prepared to take action if this becomes necessary, but that for the time being, the state budget is sufficiently capable of containing the situation. This means there are currently no plans to make cuts to the budget to cope with lower revenues.

Sovereign wealth

The big advantage that Norway has is the US$860bn (£565bn) Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global into which the oil money is deposited. Intended as an investment for future generations, it is the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world.

Norway owns an estimated 1% of global stocks and is considered to be the largest state owner of European stocks. For a country with a population just over 5m, this is a position of remarkable economic strength – thanks primarily to petroleum. The revenue of the sector is not only important as an economic boost, but also as the foundation of the Norwegian welfare state.

The government is able to spend up to 4% of the fund every year to finance its budget, albeit for investments rather than direct spending. This year, despite a substantial increase to the level of spending, it will still only run to about 3% of the total. This is also a country in which unemployment is very low – below 4%.

In short, the fall in oil prices is problematic but by no means catastrophic for Norway. The general reaction is a pragmatic one: Norway is in the hands of the global market, and will do what it can to maintain a profitable and responsible petroleum sector that serves the interests of the country. There are no illusions that the oil will last forever, or that prices must remain unnaturally high, and it is perhaps precisely these kinds of vulnerabilities that the Norwegian system safeguards against. Short-term losses are expected, but there is continued optimism for long-term gains.

*This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Author: Paul Buvarp is a PhD Candidate, School of International Relations at University of St Andrews

Image: An aerial view of the Oseberg oil platform in the Norwegian sea.

Failed States and the origins of violence

Reviewed by Martin Meeùs.

Terrorism and other forms of political violence are more present than ever in modern societies but are unequally spread around the globe. Why are some regions of the world “terrorist factories” while others are more moderate? In the view of Failed States and the Origins of Violence, by Tiffiany Howard, the FARC, Somali Al-Shabaab militants, Al-Qaeda, and the Tamil Tigers have at least one common characteristic: they were born in failing or failed states.

Howard’s study addresses the lack of consensus regarding the environmental conditions and breeding grounds that give rise to terrorism and political violence. To do so, the author tries to tackle the absence of empirical and quantitative research in the field. Her central hypothesis is that failed states are the roots of terrorism and political violence. The author insists on the novelty and uniqueness of her study, given her use of the “Global Barometer Project” to examine the reasons why certain individuals are more inclined to use political violence than others. Contrary to other macro-level studies on terrorism, not only does the author explain how weak states contribute to terrorism but also which precise features of these states encourage terrorist activities. Additionally, this study is not only descriptive but also predicative. Based upon her descriptive analysis, the author tries to determine which regions will be more inclined to give rise to terrorism and political violence in the future. The author makes ambitious predictions and goes as far as stating that sub-Saharan Africa may witness an uncontrollable level of violence never before seen.

In the first part of the book, Howard deconstructs all major existing studies on the subject of terrorist origins. She then discusses different world regions, beginning with the part of the world that encompasses the greatest number of failed states: sub-Saharan Africa. According to Howard, it is an ideal start to support her hypothesis. The second region discussed is the Middle East and North Africa, since it is the region most plagued by terrorist groups. She continues with South Asia and Southeast Asia, regions that are in-between in terms of failed states and terrorist groups. Finally, Latin America is discussed as a region that encompasses few failed states compared to the regions addressed but where violent extremism is still present.

For the four regions discussed, the author tries to empirically prove her hypothesis that failed states are breeding grounds for terrorism and political violence. The same precise and methodic approach is used in all four chapters dedicated to the four regions. First, she introduces the region at stake, its history of political violence, and the current situation. Then, she describes the variables used in order to apply her hypothesis to the particular region. These variables, which include the level of political violence, the presence of the state, or the level of security, are based upon interviews and specific questions asked of members of the population of the analyzed region. After that, she presents a logit model, which is a form of mathematical equation that evaluates the probability for individuals of each country to commit acts of political violence. Finally, she applies the logit model to the data and discusses the findings in the form of statistical results. In other words, she applies barometer survey data to logit models in order to assess the link between the failure of the states and the level of political violence.

Howard shares novel and interesting views. She argues that the promotion of democracy, modernization, and religious freedom in these regions should be addressed through state building rather than on individual bases. Regarding Islam, Howard states that there is nothing in the religion itself that favors radical ideologies and terrorism. Rather, the reason why Al-Qaeda, ISI, the Muslim Brotherhood, Fatah, or Hamas perpetrate acts of political violence is not related to the nature of Islam but rather to the inability of the governments to provide economical and social goods as well as security. Radical Islam is born with the failure of states and as a result of a repressive political climate and lack of economical development. Howard further argues that the use of political violence by an individual against Western societies and the United States, in particular, implies the support of political violence in his own state.

Thus, Howard makes interesting assumptions and hypotheses that merit discussion. However, the process employed by the author to reach these conclusions is difficult to understand. Indeed, the methodology she uses, which focuses on statistics and mathematical equations, is indigestible and unpersuasive. The reader is overwhelmed by variables, data, and numbers. Ultimately, the reader finds himself asking: is it really possible to address the relationship between state failure and terrorism through interviews that have been transformed into numbers and applied to mathematical equations?

When statistical findings do not entirely support her hypothesis, Howard tries to correct the discrepancy with more dogmatic and idealist arguments. She invokes the complexity of the states, possible cultural exceptions, or the fact that the sample used for interviews may not be representative. These are indeed crucial factors to take into account, and that is precisely the problem of this study. These are the questions that the reader wants to ask at the end of all chapters, for every region discussed. Are data from 2006 still relevant to address terrorism in South and Southeast Asia in 2014? Is a sample between 750 and 1,300 respondents from countries in the Middle East and North Africa sufficiently representative to construct a theory of the states? How can one reduce such complex societies to a couple of logit models? There are very few data sets available and the author tries her best to take the most out of them. But human sciences cannot be reduced to mathematical equations and confined to statistical data. The work is certainly unique, but the Howard’s desire for empiricism is too great and she fails to convince.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]